Trade White Paper: our future UK trade policy

Published 9 October 2017

Foreword from the Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade

Liam Fox, Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade.

As we negotiate our exit from the European Union, we have a once in a lifetime opportunity to build a stronger, fairer and more prosperous United Kingdom that is more open and outward- looking than ever before. For the first time in over 40 years, the UK will have its own independent trade policy.

Global trade has had, and continues to have, an overwhelmingly positive impact on prosperity in the UK and around the world. In the last 3 decades, commercial liberalisation has lifted more people out of abject poverty than at any other time in human history.

However, there continues to be widespread concern about the benefits of free trade and how evenly these are spread across the whole of the UK. We must recognise that whilst globalisation has spread prosperity and lifted millions out of poverty, some have felt left behind. Aligning our domestic Industrial Strategy and our trade ambitions will be key to delivering the innovative, competitive and growing economy that benefits individuals and communities, and will ensure the value of trade is shared more widely.

The UK already has a well-established and respected track-record in championing free trade from within the EU. As we exit the EU, the UK will build on this to play a leading role in the global rules-based multilateral trading system, as well as expanding our existing bilateral trading relationships.

As we develop our own independent trade policy and look to forge new and ambitious trade relationships with our partners around the world, we will build a truly Global Britain upon a strong economy with open and fair trade at its heart.

Executive summary

Preparing for our future UK trade policy

Introduction

The United Kingdom has a long and proud history as a great trading nation and champion of free trade with all parts of the world. We want to maximise our trade opportunities globally and across all countries – both by boosting our trading relationships with old friends and new allies, and by seeking a deep and special partnership with the EU.

In her speech in Florence[footnote 1], the Prime Minister set out a bold and ambitious vision for our future relationship with the EU once we have left, both in terms of the economic partnership we seek, and the security relationship. We are confident about the future for the UK and for the EU. The government has also proposed a strictly time-limited implementation period to be agreed between the UK and the EU to allow business and people time to adjust, and to allow new systems to be put in place. Such a period should ensure that the UK’s and the EU’s access to one another’s markets continues on current terms, so that people and businesses will only have to plan for one set of changes in the relationship between the UK and the EU.

The Prime Minister also underlined that the people of the UK have decided to be a global, free-trading nation, able to chart our own way in the world. Our vision is to build a future trade policy that delivers benefits not only for the UK’s economy, but for businesses, workers and consumers alike. This paper is an early step in identifying the key elements of that trade policy. In order to ensure continuity in relation to our trade around the world and avoid disruption for business and other stakeholders, the UK needs to prepare ahead of its exit from the EU for all possible outcomes of the negotiations, and ensure that we have the necessary legal powers and structures to enable us to operate a fully functioning trade policy and pursue new trade negotiations.

In assessing the options for the UK’s future customs relationship with the EU, as set out in the government’s “Future customs arrangements” (PDF, 272KB) future partnership paper[footnote 2], the government will be guided by what delivers the greatest economic advantage to the UK and by 3 strategic objectives:

- ensuring UK-EU trade is as frictionless as possible

- avoiding a ‘hard border’ between Ireland and Northern Ireland

- establishing an independent international trade policy

The government will take forward these objectives in our negotiation with the EU. This paper explores our emerging approach to the third of these objectives: establishing an independent international trade policy.

This paper has 2 parts: the first part outlines the world in which the UK trades and the role of trade in an economy that works for everyone. The second part outlines the basic principles that will shape our future trading framework, and our developing approach to our trade policy. This includes 5 key components, and some specific areas where we are preparing the necessary legal powers now to ensure we are ready to operate independently as we exit the EU. The paper welcomes views both on the specific legal powers we are seeking in this first step and on our broader developing approach.

The role of trade in an economy that works for everyone

Trade is a key driver of growth and prosperity and has always been an important part of both the UK and world economy. Our total trade with the world is equivalent to over half of our GDP – exports and imports were each equivalent to about 30% of GDP in 2016. International trade is linked to many jobs; it can lead to higher wages and can contribute to a growing economy by stimulating greater business efficiency and higher productivity, sharing knowledge and innovation across the globe. It ensures more people can access a wider choice of goods at lower cost, making household incomes go further, especially for the poorest in society.

Trade enables countries, firms and individuals to specialise in economic activities that play to their relative strengths, abilities, resources and expertise, and to buy from and sell to other countries doing likewise. Specialisation increases global output and increases the quality and value of goods and services for consumers. Businesses that export into new markets can access more customers and help to grow overall UK exports, which contribute to growth in the UK economy. For example, our world leading automotive and creative industries would benefit from the opening up of new international markets which would support growth in these sectors.

The positive impacts of trade for producers and consumers, importers and exporters, are numerous, but the benefits are not always universally felt. Despite trade increasing prosperity and living standards, some sectors, regions and groups experience the, often more concentrated, adjustment effects of trade. We will work with all stakeholders to ensure the benefits of trade can be widely felt and understood, managing the transition brought about by changes in the trade environment. Our approach to trade will align with our Industrial Strategy. That will be key to delivering an innovative, competitive and growing UK economy that benefits individuals and communities and makes sure the value of trade is more widely shared.

Our approach

In order to ensure continuity in relation to our trade around the world and avoid disruption for business and other stakeholders, the UK needs to prepare ahead of its exit from the EU, for all possible outcomes of negotiations, and to ensure that we have the necessary legal powers and structures to enable us to operate a fully functioning trade policy as we leave the EU.

There are several key elements of this future trade policy, which will combine to deliver benefits to all parts of the UK and contribute to an economy that works for everyone. This paper outlines those elements, our principles, initial priorities and approach to preparation of the framework that will deliver on these opportunities.

Trade that is transparent and inclusive

Our approach to developing our future trade policy must be transparent and inclusive. Parliament, the devolved administrations, the devolved legislatures, local government, business, trade unions, civil society, and the public from every part of the UK must have the opportunity to engage with and contribute to our trade policy. We will also take into account the views of the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, including Gibraltar.

The government is undertaking a comprehensive stakeholder engagement programme as part of our preparations for the UK’s exit from the EU.

Supporting a rules-based global trading environment

The UK has long been, and remains, a strong supporter of an open, rules-based international trading system. Such a system can create benefits felt well beyond those we experience in the UK. It enables economic integration and security cooperation, encourages predictable behaviour by states and the peaceful settlement of disputes. It can lead states to develop political and economic arrangements at home which favour open markets, the rule of law, participation and accountability.

The UK is a full and founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and has consistently supported its efforts to liberalise trade and enforce international trade rules. The UK is already a powerful pro-trade advocate and proponent of the multilateral system. When we leave the EU we will regain our independent seat at the WTO. As an independent member and one of the largest economies in the world, we will be in a position to intensify our support for robust, free and open international trade rules which work for all, and to help to rebuild global momentum for trade liberalisation. As part of our commitment to the rules-based global system and the benefits it brings, we will take specific steps as we leave the EU to ensure the UK remains part of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA).

Boosting our trade relationships

As we leave the EU and develop our own trade policy, the government is committed to ensuring that UK and EU businesses and consumers can continue to trade freely with one another, as part of a new deep and special partnership. We will also boost our trade relationships with old friends and new allies. As the European Commission’s own ‘Trade for All Strategy’ suggests, 90% of global economic growth in the next 2 decades will come from outside the EU[footnote 3], so it is likely that a greater proportion of UK trade will continue to be with non-EU countries.

The UK will look to secure greater access to overseas markets for UK goods exports as well as push for greater liberalisation of global services, investment and procurement markets. We will also seek ambitious digital trade packages, including provisions supporting cross-border data flows, underpinned by appropriate domestic data protection frameworks.

Any new trade arrangements and trade deals will ensure markets remain open and fair behind the border. We will maintain a high level of protection for intellectual property, consumers, the environment, and employees. We will ensure that decisions about how public services, including the NHS, are delivered for UK citizens are made by the UK government or the devolved administrations.

As the Prime Minister set out in her speech in Florence, the UK will seek to agree a time-limited implementation period with the EU, during which access to one another’s markets should continue on current terms. This would help both the UK and EU to minimise unnecessary disruption and provide certainty for businesses and individuals as we move towards our future deep and special partnership with the EU. The UK would intend to pursue new trade negotiations with others during the implementation period, having left the EU, though we would not bring into effect any new arrangements with third countries that were not consistent with the terms of our agreement on an implementation period with the EU.

As we prepare to leave the EU, we will seek to transition all existing EU trade agreements and other EU preferential arrangements. This will ensure that the UK maintains the greatest amount of certainty, continuity and stability in our trade and investment relationships for our businesses, citizens and trading partners.

Supporting developing countries to reduce poverty

The UK government has a long-standing commitment to support developing countries to reduce poverty through trade. The government will continue to deliver improved support in the future by helping those developing countries break down the barriers to trade. This will help them to continue to benefit from trade by growing their economies, increasing incomes and reducing poverty. Helping to build developing countries’ prosperity creates the conditions that allow commerce to flourish and in doing so, opens up opportunities for UK business in future markets.

One important way in which trade can support developing countries is providing preferential access for them, where generally applicable tariffs are in place. Easier access to the markets of developed countries provides vital opportunities for the world’s poorest countries to help grow their economies and reduce poverty, whilst UK business and consumers rely on these relationships for lower cost goods and greater choice of products.

As we leave the EU, we recognise the need for a smooth transition not only for the UK but also for developing countries. It is therefore important that the UK is ready to put in place a trade preferences scheme, which will, as a minimum, provide the same level of access as the current EU trade preference scheme. This will ensure that the world’s poorest countries can still benefit from duty-free access to UK markets, and that other developing countries across the globe can continue to export to the UK accordingly.

Ensuring a level playing field – a UK approach to trade remedies and trade disputes

Free trade does not mean trade without rules. To operate an independent trade policy, we will need to put in place a trade remedies framework. As an important part of a rounded trade policy, a trade remedies framework is designed to protect domestic industry against unfair and injurious trade practices, or unexpected surges in imports by allowing for measures (usually a duty) to be placed on imports of specific products. Consistent with our WTO obligations, the UK’s framework will be implemented by a new mechanism to investigate cases and propose measures that offer proportionate protections for our producers. In preparation for this, we also need to identify existing EU measures which are essential to UK business and will need to be carried forward. We will shortly be issuing a call for evidence as a first step towards identifying which existing trade remedies measures have a UK interest.

In addition, the WTO’s existing trade dispute settlement mechanism aims to resolve trade conflicts between countries and, by underscoring the rule of law, makes the international trading system more predictable and secure. The European Commission currently manages trade disputes on our and other member states’ behalf. By the time we leave the EU, we will ensure we are ready to act independently to protect UK interests should our trading partners fail to meet their international obligations and to defend any disputes brought against the UK.

Next steps

As we continue our work to develop and deliver a UK trade policy that benefits business, workers and consumers across the whole of the UK, we will engage regularly with stakeholders through both formal and informal consultation mechanisms. Through this paper we are seeking views on all aspects of our developing approach. In particular, we invite feedback on the following elements, as part of our engagement on the legislation (including a trade bill and a customs bill) which the government intends to introduce in this parliamentary session:

- our commitments to an inclusive and transparent trade policy

- our approach to unilateral trade preferences

- our approach to trade remedies

Feedback should be sent to stakeholder.engagement@trade.gov.uk by 6 November.

Introduction

The United Kingdom has a long and proud history as a great trading nation and champion of free trade with all parts of the world. We want to maximise our trade opportunities globally and across all countries – both by boosting our trading relationships with old friends and new allies, and by seeking a deep and special partnership with the EU.

In her speech in Florence, the Prime Minister set out a bold and ambitious vision for our future relationship with the EU once we have left, both in terms of the economic partnership we seek, and the security relationship. We are confident about the future for the UK and for the EU. The government has also proposed a strictly time-limited implementation period to be agreed between the UK and the EU to allow business and people time to adjust, and to allow new systems to be put in place. Such a period should ensure that the UK’s and the EU’s access to one another’s markets continues on current terms, so that people and businesses will only have to plan for one set of changes in the relationship between the UK and the EU.

The Prime Minister also underlined that the British people have decided to be a global, free-trading nation, able to chart our own way in the world. Our vision is to build a future trade policy that delivers benefits not only for the UK’s economy, but for businesses, workers and consumers alike. This paper is an early step in identifying the key elements of that trade policy. In order to ensure continuity in relation to our trade around the world and avoid disruption for business and other stakeholders, the UK needs to prepare ahead of its exit from the EU for all possible outcomes of the negotiations, and ensure that we have the necessary legal powers and structures to enable us to operate a fully functioning trade policy and pursue new trade negotiations.

In assessing the options for the UK’s future customs relationship with the EU, as set out in the government’s ‘Future customs arrangements’ future partnership paper, the government will be guided by what delivers the greatest economic advantage to the UK and by 3 strategic objectives:

- ensuring UK-EU trade is as frictionless as possible

- avoiding a ‘hard border’ between Ireland and Northern Ireland

- establishing an independent international trade policy

The government will take forward these objectives in our negotiation with the EU. This paper explores our emerging approach to the third of these objectives: establishing an independent international trade policy.

This paper has 2 parts: the first part outlines the world in which the UK trades and the role of trade in an economy that works for everyone. The second part outlines the basic principles that will shape our future trading framework, and our developing approach to our trade policy. This includes 5 key components, and some specific areas where we are preparing the necessary legal powers now to ensure we are ready to operate independently as we exit the EU. The paper welcomes views both on the specific legal powers we are seeking in this first step and on our broader developing approach.

Decisions on trade policy are currently taken by the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament in their roles as representatives of EU member states, and the day to day conduct of trade relations of EU member states, including the negotiation of free trade agreements, is led by the European Commission.

While we are members of the EU, we will continue to comply fully with our obligations and to engage constructively with our partners. The steps we are taking to introduce trade legislation will not at this point affect our trade relationships with third countries, the operation of the Common Commercial Policy of the EU, or the international trading frameworks within which the UK operates as a member of the EU. As we leave the EU, we will remain committed to working collaboratively with the EU to take forward our shared free trade agenda.

As the Prime Minister set out in her speech in Florence, the UK will seek to agree a strictly time-limited implementation period with the EU, during which access to one another’s markets should continue on current terms. This will support certainty and stability for business as we move towards the deep and special relationship. The UK would intend to pursue new trade negotiations with others during the implementation period, having left the EU, though it would not bring into effect any new arrangements with third countries that were not consistent with the terms of its agreement on an implementation period with the EU.

Legislation

In order to ensure continuity in relation to our trade around the world and avoid disruption for business and other stakeholders, the UK needs to prepare ahead of its exit from the EU for all possible outcomes of negotiations and ensure that we have the necessary legal powers and structures to enable us to operate a fully functioning trade policy after our withdrawal from the EU. We are introducing legislation (including a trade bill and a customs bill) that:

- enables continuity in the UK’s current trade and investment relationships

- enables the UK to implement obligations that arise under the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) (the UK will need to be able to implement these obligations in order to join the GPA as an independent member in our own right)

- creates a UK trade remedies framework that addresses unfair and injurious trade practices, or unexpected surges in imports, and is consistent with our World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations

- enables the UK to enforce or abide by the outcomes of international trade disputes

- creates a unilateral UK trade preferences scheme to enable the UK to continue to provide preferences that support economic and sustainable development in the world’s poorest countries, as part of our wider development agenda

- provides a gateway to facilitate the collection and sharing of data which the Department for International Trade requires as it takes on functions previously performed by the EU Commission. For example, in order for the Department for International Trade to collect the same data on intra- and extra-EU trade in goods as we do now

These are first steps relating to certain specific powers that will be needed in the period ahead. The government also intends to introduce legislation that would allow the UK to operate standalone customs and indirect tax regimes as we withdraw from the EU. This will include the power to set customs duties, tariff rate quotas and preferences, as well as wider tariff-related provisions.

As we leave the EU, we will also need new legal powers to maintain our ability to impose, implement and amend trade sanctions regimes, which are an important foreign policy and national security tool. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office published a White Paper on the UK’s future legal framework for imposing and implementing sanctions on 21 April 2017[footnote 4]. This was followed by the announcement in the Queen’s Speech of a Sanctions Bill to be introduced in this parliamentary session.

The role of trade in an economy that works for everyone

Trade is a key driver of growth and prosperity and has always been an important part of both the UK and world economy. Our total trade with the world is equivalent to over half of our GDP - exports and imports were each equivalent to about 30% of GDP in 2016. International trade is linked to many jobs; it can lead to higher wages and can contribute to a growing economy by stimulating greater business efficiency and higher productivity, sharing knowledge and innovation across the globe. It ensures more people can access a wider choice of goods at lower cost, making household incomes go further, especially for the poorest in society.

The positive impacts of trade for producers and consumers, importers and exporters, are numerous, but the benefits are not always universally felt. Despite trade increasing prosperity and living standards, some sectors, regions and groups experience the, often more concentrated, adjustment effects of trade. We will work with all stakeholders to ensure the benefits of trade can be widely felt and understood, managing the transition brought about by changes in the trade environment. Our approach to trade will align with our Industrial Strategy. That will be key to delivering an innovative, competitive and growing UK economy that benefits individuals and communities and makes sure the value of trade is more widely shared.

Cargo ships.

1. Global economic context

Free and fair trade is fundamental to the prosperity of the UK and the world economy. It is an essential part of our plan to deliver a country that is stronger, fairer, more united and more outward-looking than ever before. And our future trade policy will have wider implications – for the UK’s global reputation and influence, our bilateral relationships, and our ability to deliver our international interests.

Trade has always been an important part of the UK economy. Excluding major shocks such as the Great Depression and 2 World Wars, exports and imports have each generally been equivalent to over 20% of UK GDP for the last 160 years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Importance of trade for the UK over the last 200 years

Figure 1: Importance of trade for the UK over the last 200 years [footnote 5]

1.1 Emerging trends

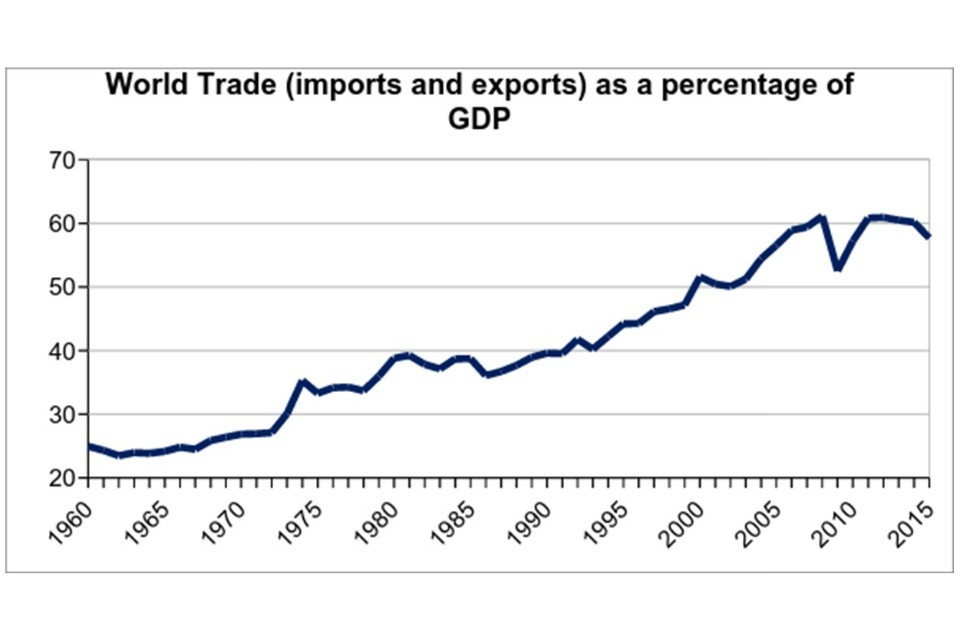

Over the last half century, trade has become increasingly important. Liberalisation has made trade cheaper and more predictable. Technological progress has made trade easier. As a result, global goods exports are now 38 times higher than they were in 1950[footnote 6] and as the chart below shows, world trade as a percentage of the global economy has more than doubled since 1960.

Figure 2: Trade's increasing share of world GDP

Figure 2: Trade’s increasing share of world GDP[footnote 7]

A substantial proportion of the growth in global trade in recent decades has been driven by 2 trends. Firstly, the growth in intra-industry trade; intra-industry trade (the import and export of the same or similar goods) has increased from around 70% in the late 1980s to over 80% between 1997 and 2008; over 80% of UK manufacturing trade was intra-industry[footnote 8].

Secondly, the development of cross-border supply chains, where different stages of production for a particular good are located in different countries. Well-functioning global trade relationships help UK businesses to manage their supply chains effectively and source the imports they need. Over 70% of global trade is now in intermediate products, or in capital goods (many of which will be employed in the production of other goods[footnote 9]).

This has driven some significant shifts in shares of world trade. Developed economies’ share of global exports fell from 69% in 1980 to 54% in 2013. Much of the corresponding growth in developing countries’ share of global trade was accounted for by China, whose share of global exports rose from 1% in 1982 to 10% in 2013, but there has also been significant growth in the share of developing economies across Asia[footnote 10]. These trends are expected to continue. Approximately 90% of global economic growth in the next 10 to 15 years is expected to be generated outside Europe[footnote 11].

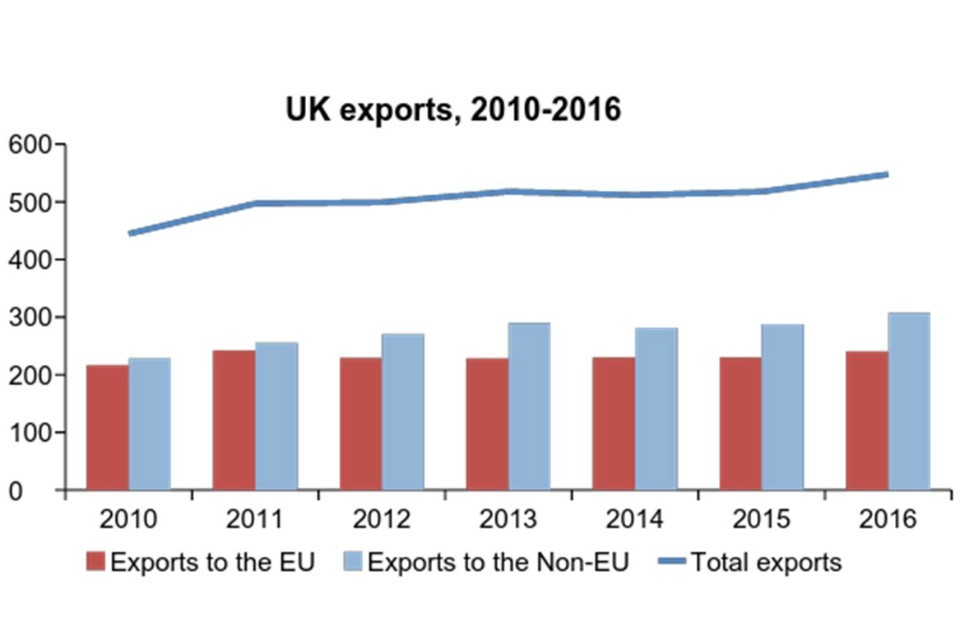

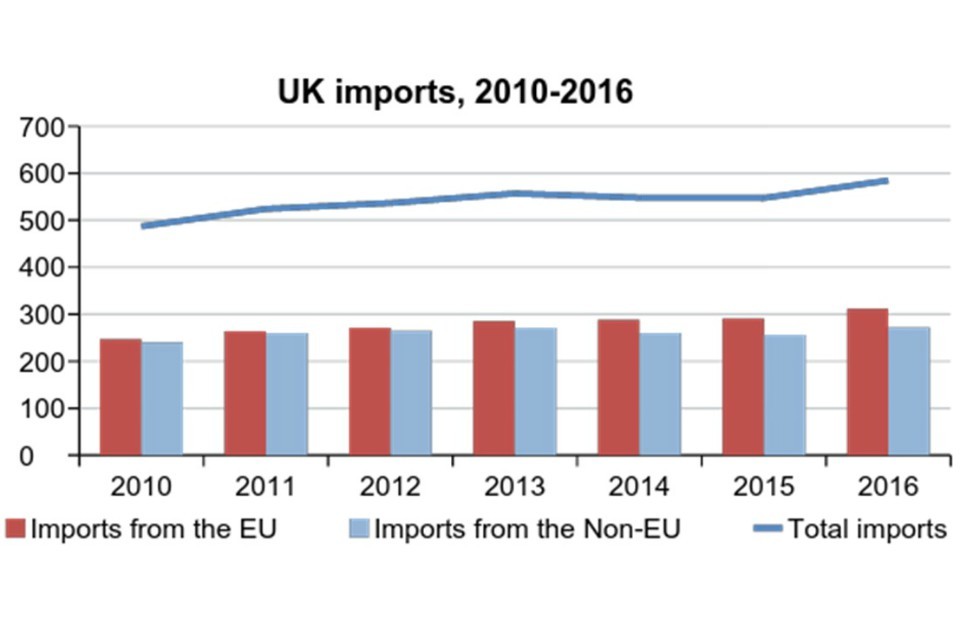

Between 2010 and 2016, the value of UK goods exports has grown by 12%, but the value of UK services exports by 40%[footnote 12], with services accounting for around 45% of the value of UK exports in 2016[footnote 13]. Trade in services represents around 20% of the value of world trade[footnote 14]. Moreover, according to the OECD, services make up over 30% of the value of manufacturing exports[footnote 15].

Services are also an important, and growing, component of supply chains. Firms increasingly use integrated logistics, communications services, and business services to enable the efficient functioning of their supply chains, and almost one third of the value of manufactured exports of developed countries represents service value added[footnote 16]. Digital technology is continuing to develop rapidly, facilitating economic growth and making more and more services tradable[footnote 17]. In this context, the UK services industry is also a global leader in the development of innovative trade facilitators, such as financial technology and new financial products. The UK generated £6.6 billion of revenue in the high growth end of the FinTech sector in 2015[footnote 18].

Figure 3: Broad stability of UK exports 2010-16

Figure 3: Broad stability of UK exports 2010-16

Figure 4: Broad stability of UK Imports 2010-16

Figure 4: Broad stability of UK Imports 2010-16[footnote 19]

Trade agreements at the multilateral, plurilateral and bilateral level help to facilitate international trade for the UK. When we leave the EU, we will seek opportunities to pursue an ever more ambitious global trade agenda, to maximise our trade opportunities globally and across all countries – both by boosting our trading relationships with old friends and new allies, and by seeking a deep and special partnership with the EU.

1.2 Global trade growth slowdown

Despite historic trends, both global economic growth and global trade growth have decelerated in recent years. Global trade growth has grown at about half its long run rate in recent years. Since January 2015 world trade volumes have plateaued[footnote 20], unusually outside global recession.

Although the WTO is currently forecasting a modest rebound in 2017 and 2018, structural factors suggest that growth in global trade is unlikely to return to the high growth rates of the last 30 to 40 years and should be expected to grow more in line with income in the years ahead[footnote 21].

The slowdown in global trade growth is the symptom of a number of factors. OECD analysis has suggested that the slowdown is due to both cyclical factors, notably reduced growth in the global economy and investment since the financial crisis, and to structural factors, such as a slowdown in the growth of global value chains and rising protectionism. The UK needs an ambitious trade policy to counter these trends.

1.3 Protectionist measures

In recent years, the use of protectionist measures has been increasing around the world. Protectionist measures are interventions that unreasonably restrict or increase the cost of trade and investment by discriminating against overseas firms. They can include subsidies and bailouts for domestic industry in addition to more conventional measures, such as new or increased tariffs, customs regulations and rules of origin restrictions on trading partners[footnote 22].

Some reasonable trade protection interventions can be warranted, for example if they are time-limited, proportionate and well designed to address genuinely unfair practices, such as state-assisted subsidies and dumping used by third countries. However, any such interventions must be balanced with the needs of the wider economy[footnote 23]. Protectionist measures in general distort markets, harm global trade, and slow global growth. In addition to ensuring a balanced and proportionate approach to trade protection interventions, we will intensify our efforts to be a global champion for free trade and make the most of new opportunities to push for greater liberalisation.

2. Making trade work for everyone

Free and open trade has had, and continues to have, an overwhelmingly positive impact on prosperity around the world and has taken more people out of abject poverty in the last 25 years [footnote 25] than in the whole of human history. However, we recognise that some areas and sectors may benefit from trade liberalisation more than others, while some people feel left behind. Likewise there is a feeling that increased openness to trade may threaten our protections, including consumer safety standards and public services.

The proper response to these concerns is not to turn our backs on international trade. The challenge is clear: to make sure the whole of the UK is able to take full advantage of the opportunities that trade offers. It is for this reason that the government has committed to building a global economy that works for everyone.

We will ensure the way we develop our own trade policy is transparent and inclusive so that concerns are heard and understood, and the right facts are available. Parliament, the devolved administrations, devolved legislatures, local government, business, trade unions, civil society, consumers, employees and the public from every part of the UK will have the opportunity to engage with and contribute to our trade policy, to develop an approach which maximises the benefits felt across UK society and its regions. We will also take into account the views of the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, including Gibraltar.

Through our trade remedies measures we will ensure that our domestic industries do not suffer harm as a result of distortions of international trade caused by dumping or subsidy. This helps ensure a level playing field, upon which our Industrial Strategy will allow UK-based industries to thrive, by adapting to and embracing emerging trends to stay at the cutting edge.

Our Industrial Strategy will be designed to develop an economy that works for everyone: an economy that delivers good, skilled, well-paid jobs and creates the conditions for competitive, world-leading businesses to prosper and grow across all parts of the UK. Through it, the government will continue to demonstrate a strong commitment to trade and investment, to build on our strengths and improve vital areas such as science, infrastructure, and research and innovation – so that the benefits of trade help deliver wealth and opportunity across the country.

2.1 Choice, value and quality for consumers

Free trade has brought many benefits to our society, ensuring that more people can access a wider choice of goods at lower cost, making household incomes go further. For consumers, imports have a significant impact on daily life – through the variety of choice and price of goods available – and therefore on overall living standards.

Free trade benefits consumers and households directly through the impact that lower tariffs have on the price of imported goods and indirectly through the associated productivity gains of domestic and foreign firms. For example, during 1996 to 2006, import prices for textiles and clothing fell by 27% and 38% respectively in real terms, in large part as a result of the phasing out of restrictive quotas which had greatly limited access to most developed countries’ markets for textiles and clothing. For the same period, the import price of consumer electronics fell by around 50%[footnote 25] reflecting the impact of the WTO’s Information Technology Agreement – a plurilateral agreement concluded in 1996 which provides tariff free access for various IT products and which has now expanded to cover around 97% of global trade in these IT products.

Free trade drives domestic businesses to innovate and move up the value chain to compete with cheaper imports in order to set themselves apart, which means that consumers benefit from better quality and ever improving products, at lower prices. This in turn ensures that household incomes go further.

Trade agreements enable countries to agree and strengthen consumer standards. The government is fully committed to ensuring the maintenance of high standards of consumer, worker and environmental protection in trade agreements

Our approach

As the UK prepares to leave the EU, we are developing our approach to deliver our own trade policy that is well-placed to reflect the needs and potential of the whole of the UK. We have a well-established and respected track-record in championing free trade from within the EU. As we exit the EU, the UK will build on this and play a proactive role in the global rules-based multilateral trading system, as well as building on and expanding existing bilateral trading relationships, and having the opportunity to take unilateral action where appropriate.

In order to ensure continuity in relation to our trade around the world and avoid disruption for business and other stakeholders, the UK needs to prepare ahead of its exit from the EU for all possible outcomes of negotiations and to ensure that we have the necessary legal powers and structures to enable us to operate a fully functioning trade policy after our withdrawal from the EU.

Our future trade policy principles

The overarching objective of our new trade policy is enhanced economic prosperity for the UK, through the development and delivery of a UK trade policy that delivers benefits for business, workers and consumers across the whole of the UK. In doing this, the government commits to the following underlying principles. The UK will:

- pursue economic prosperity for the UK and lead by example through our liberal economy and pursuit of free trade

- develop, support and enforce a fair and proportionate rules-based system for trade, domestically and internationally

- develop a trading framework which supports foreign and domestic policy, sustainability, security, environmental and development goals

- develop a trade agenda that is inclusive and transparent

1. Trade that is transparent and inclusive

Our approach to developing our future trade policy must be transparent and inclusive. Parliament, the devolved administrations, the devolved legislatures, local government, business, trade unions, civil society, and the public from every part of the UK must have the opportunity to engage with and contribute to our trade policy. We will also take into account the views of the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, including Gibraltar.

The government is undertaking a comprehensive stakeholder engagement programme as part of our preparations for the UK’s exit from the EU.

In developing our future trade policy, we are engaging regularly with our stakeholders, for example through dialogues with the Secretary of State for International Trade, Ministerial roundtables and ‘town hall’ style stakeholder briefing sessions. But we are sure that there are ways in which this can be improved and are looking for input and proposals in this area accordingly.

The devolved administrations will have a direct interest in our future trade agreements. We will work closely with them to deliver an approach that works for the whole of the UK, reflecting the needs and individual circumstances of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and drawing on their essential knowledge and expertise. We recognise that if we are to represent the UK effectively on the international stage, we must build support for our vision across all 4 nations and deliver real, tangible benefits. The Department for International Trade has worked successfully alongside the Scottish Government, Welsh Government, and Northern Ireland Executive and their agencies in promoting trade and investment activity and we intend to continue this collaborative approach as we develop the UK’s future trade policy.

To achieve this, we make the following commitments with regards to our future trade policy:

- to continue to respect the role of Parliament, and the importance of the business and the wider stakeholder community in preparing for and giving effect to an independent UK trade policy

- to seek the input of the devolved administrations to ensure they influence the UK’s future trade policy, recognising the role they will have in developing and delivering it

- to take views from all the English regions to acknowledge the important part they will play in the future prosperity of the UK

- to seek the input of all stakeholders to ensure we design the most effective mechanisms for engaging with them

- to build our understanding of the interests, attitudes and concerns about our future trade policy – across Parliament, the devolved administrations, devolved legislatures, local government, business, trade unions, civil society, and the public from every part of the UK

- to put the Industrial Strategy at the heart of our trade policy, to build a global economy that works for everyone; and

- to ensure that our commitment to scrutiny and engagement that is inclusive, meaningful and transparent is coherent with the need to ensure we do not undermine our negotiating position

We will be engaging all of these groups in the coming months, for example, through a series of subject-specific roundtables, online moderated debates and Chatham House discussion groups, to develop the right mechanisms for securing their input in future.

We are inviting views on these commitments, and the mechanisms to deliver them, as we develop our approach.

Please send responses by 6 November to stakeholder.engagement@trade.gov.uk.

2. Supporting a rules-based global trading environment

The UK has long been, and remains, a strong supporter of an open, rules-based international trading system. Such a system can create benefits felt well beyond those we experience in the UK. It enables economic integration and security cooperation, encourages predictable behaviour by states and the peaceful settlement of disputes. It can lead states to develop political and economic arrangements at home that favour open markets, the rule of law, participation and accountability.

The UK is a full and founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and has consistently supported its efforts to liberalise trade and enforce international trade rules. The UK is already a powerful pro-trade advocate and proponent of the multilateral system. When we leave the EU we will regain our independent seat at the WTO. As an independent member and one of the largest economies in the world, we will be in a position to intensify our support for robust, free and open international trade rules which work for all, and to help to rebuild global momentum for trade liberalisation. As part of our commitment to the rules-based global system and the benefits it brings, we will take specific steps as we leave the EU to ensure the UK remains part of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA).

Outside the WTO in Geneva.

2.1 Supporting the World Trade Organization

Built on agreements signed by the bulk of the world’s trading nations, the WTO is the only institution providing a near-global, rules-based system for international commerce. The WTO provides a place for monitoring the application of international trade agreements and for disputes to be settled. It also provides a place for negotiations to deliver further liberalisation of global trade. For these reasons, the WTO is essential. The UK has long been, and remains, a core proponent of the WTO both by supporting its place in the global system and ensuring that it remains relevant and effective in improving the global environment for trade.

In the short term, we are determined that the 11th Ministerial Conference of the WTO in December 2017 is a success, building on the success of recent WTO Ministerial Conferences which have led to high impact outcomes such as the ‘Trade Facilitation Agreement’ which the UK pushed for and entered into force in February 2017. It is an excellent example of recent multilateral liberalisation achieved at the WTO. Estimates suggest it could add over £70 billion to the global economy annually[footnote 26].

Longer term, we will continue to work within the WTO to promote global action to cut red tape across borders, phase out distortive subsidies, scrap tariffs on trillions of dollars’ worth of trade, and work to ensure the rule book stays relevant as patterns of trade change and technological innovations develop[footnote 27]. We will do this all firmly in the belief that the WTO should remain central to the liberalisation and governance of international trade.

Already a champion of multilateral trade from within the EU, the UK is preparing to take on an even greater role in the WTO outside the EU, but still firmly alongside our partners. The UK will be a proactive and responsible actor at the WTO, building alliances around the world to forge progress. A key part in preparing for our new position in the WTO and this enhanced role is establishing UK-specific commitments in UK-only ‘schedules’ on trade in goods and services. In order to minimise disruption to trade, the government has announced it will, as far as possible, replicate its existing commitments as set out in the EU’s schedules of commitments and submit these for certification in the WTO ahead of leaving the EU. The government will maintain current levels of market access and keep changes to a technical nature. The government stands ready to work with the EU and with other WTO Members in order to ensure a smooth transition.

2.2 Participating in plurilateral arrangements

In addition to progress at the fully multilateral level, the UK is prepared to participate in ‘plurilateral’ arrangements in the WTO – trade negotiations between a subset of the WTO Membership – when progress at the multilateral level is not possible. One such plurilateral agreement already in force is the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). We will take specific steps to ensure the UK remains part of the GPA when we leave the EU. This includes legislating to enable the UK to make any changes required in domestic legislation before the UK accedes to the GPA, and to have the power to make changes in the future, for example, to reflect new countries joining the GPA. This would allow UK businesses to keep guaranteed non-discriminatory access to a public procurement market estimated to be worth over £1.3 trillion annually. Where we have chosen to open the UK’s public procurement market to international competition, the UK also benefits from increased choice and value for money. Parliamentary approval for ratifying the UK’s independent membership of the GPA will be sought separately.

We support the finalisation of the Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) being negotiated under the WTO framework. Once agreed, the EGA would remove tariffs on an agreed list of around 250 products that provide environmental benefits and include a review mechanism allowing for new environmental technologies to be added as they are developed, boosting innovation. The UK has been a strong supporter throughout the negotiation process due to the contribution the EGA will make towards tackling climate change and supporting sustainable growth. We have continued to support any efforts to take the negotiation process forward towards final agreement.

We strongly support the conclusion of the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations and the UK will continue to play an active role as we work towards becoming a member of TiSA in our own right. While TiSA is being negotiated outside the WTO framework, it has the potential to advance the global standards of services trade, setting ambitious new rules and harnessing the liberalisation of trade in services achieved in the last 2 decades. With services accounting for around 45% of the value of UK exports in 2016[footnote 28], we support TiSA negotiations being resumed as soon as possible, securing a better deal for UK businesses over and above existing WTO rules.

2.3 Championing free trade globally

We will be a leading advocate of free trade on the world stage; taking a dynamic and proactive position at the WTO once we have left the EU, and working with our partners through other international organisations and bodies such as the OECD and UN. We will work with like-minded governments and through groups such as the G7 and G20 to advocate free trade and open markets, to make the international trading system work better, and to build a global economy that works for everyone.

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 2018 will be an important opportunity to highlight the UK’s role as a champion for global free trade and to develop the UK’s work with Commonwealth partners to deliver mutual prosperity objectives. The Commonwealth is home to a third of the world’s population, many of its fastest growing economies, and half of the globe’s top 20 emerging cities. This vast network of growing markets, with which the UK has long-established relationships, presents a significant opportunity for UK business and enhances the UK’s ability to promote free trade in a multilateral rules-based system.

3. Boosting our trade relationships

As we leave the EU, and develop our own trade policy, the government is committed to ensuring that UK and EU businesses and consumers can continue to trade freely with one another, as part of a new deep and special partnership. We will also boost our trade relationships with old friends and new allies. As the European Commission’s own ‘Trade for All Strategy’ suggests, 90% of global economic growth in the next 2 decades will come from outside the EU , so it is likely that a greater proportion of UK trade will continue to be with non-EU countries.

The UK will look to secure greater access to overseas markets for UK goods exports as well as push for greater liberalisation of global services, investment and procurement markets. We will also seek ambitious digital trade packages, including provisions supporting cross-border data flows, underpinned by appropriate domestic data protection frameworks.

Any new trade arrangements and trade deals will ensure markets remain open and fair behind the border. We will maintain a high level of protection for intellectual property, consumers, the environment, and employees. We will ensure that decisions about how public services, including the NHS, are delivered for UK citizens are made by the UK government or the devolved administrations.

As the Prime Minister set out in her speech in Florence, the UK will seek to agree a time-limited implementation period with the EU, during which access to one another’s markets should continue on current terms. This would help both the UK and EU to minimise unnecessary disruption and provide certainty for businesses and individuals as we move towards our future deep and special partnership with the EU. The UK would intend to pursue new trade negotiations with others during the implementation period, having left the EU, though we would not bring into effect any new arrangements with third countries that were not consistent with the terms of our agreement on an implementation period with the EU.

As we prepare to leave the EU, we will seek to transition all existing EU trade agreements and other EU preferential arrangements. This will ensure that the UK maintains the greatest amount of certainty, continuity and stability in our trade and investment relationships for our businesses, citizens and trading partners.

3.1 Trading with the EU

The UK government is committed to securing a deep and special partnership with the EU, including a bold and ambitious economic partnership. The UK wants to secure the freest trade possible in goods and services between the UK and the EU.

A close trading relationship benefits both the UK and EU member states. As a bloc the EU accounts for the largest single proportion of UK trade. In 2016, UK imports from and exports to the EU totalled £553 billion[footnote 29], with over 200,000 UK businesses trading in goods with the EU[footnote 30].

Furthermore, UK-EU trade is an important contributor to the economy in all parts of the UK. Close trading relationships with the EU exist across a range of sectors, which employ millions of people around Europe. Producers in other EU member states also rely on UK firms in their supply chains and vice versa. After we exit the EU we want to maximise our trade opportunities globally, both by boosting our trading relationships with old friends and new allies, while at the same time having the greatest possible tariff-and-barrier-free trade with the EU.

3.2 Trading with the rest of the world

The UK currently enters into commitments in international trade agreements as a member of the EU. This includes Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), development-focused Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), plurilateral agreements and the suite of agreements and disciplines which form our obligations under the WTO.

Transitioning EU third country trade agreements

The UK government is committed to seeking continuity in its current trade and investment relationships, including those covered by EU third country FTAs and other EU preferential arrangements. We aim to deliver certainty for UK businesses and consumers following EU exit, as well as ensuring continued tariff preference arrangements for developing countries concerned. This includes introducing measures through legislation which will allow the government to fully implement any EU third country and other EU preferential arrangements which we transition.

As parts of these agreements will touch on devolved matters, legislation will create powers for devolved administrations to implement them. These powers will be held concurrently by the devolved administrations and the UK government. This approach will ensure that, where it makes practical sense for regulations to be made once for the whole UK, it is possible for this to happen. The UK government will not normally use these powers to amend legislation in devolved areas without the consent of the relevant devolved administrations, and not without first consulting them. These powers will help to ensure continuity of our current trade and investment arrangements, support business certainty, provide greater flexibility, minimise legal risk, and reduce the volume of legislation resulting from EU exit. These powers, which are being taken in the trade legislation, will be used for the purposes of transitioning existing agreements signed before EU exit. Decisions have not yet been taken on the legislative framework for the implementation of future agreements. More information on future agreements is below.

Negotiating and implementing new trade agreements

When we leave the EU, we will seek opportunities to pursue an ever more ambitious free trade agenda. However as noted above, we would not bring into effect any new arrangements with third countries which were not consistent with the terms of our agreement with the EU.

In preparation for a range of scenarios with the EU, we have been considering what we will need to put in place to ensure that the process of negotiating and implementing new trade deals is transparent, efficient and effective. We want to make provision for a legislative framework that will enable future trade agreements with partner countries to move quickly from signing to implementation and then to ratification, whilst respecting due process in Parliament.

Equally importantly, we will ensure that Parliament, the devolved administrations, devolved legislatures, business and civil society are engaged throughout. We think it is vital to consider the process in the round. We will be consulting on these issues in due course, and we will commit to working with the devolved administrations on our approach to the implementation of trade agreements signed after EU exit, as well as the role they will play in shaping the UK’s future trade negotiations.

3.3 Improving our bilateral trading relationships

We start from a position of strength. We already have a range of trade relationships in place with different markets, and will continue to improve and progress our bilateral trading relationships. There are many ways in which the UK can strengthen its trade and investment relationships with partners across the world. One important way is to agree a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and a number of countries have shown a keen interest in doing so. But a range of options is available to us, from discrete bilateral agreements to broader regional types of partnerships. We will examine the range of relationships that are appropriate and available to us, drawing on best practice from the EU and elsewhere.

We already conduct regular Ministerial dialogues, such as Joint Economic and Trade Committees (JETCOs) and Economic and Financial Dialogues (EFDs) with a wide range of markets. These dialogues will become even more valuable after Brexit with the potential to cover a broader range of trade policy and market access issues than is currently the case. We can also conduct trade reviews with the aim of strengthening a bilateral relationship by identifying options to overcome barriers to trade, improving our links in the immediate future, and laying the ground work to develop future long-term trade relationships. For example, we are starting to undertake a trade review with India.

Through our global Department for International Trade network, we will continue to work with businesses to identify the key market access barriers they encounter in export markets and prioritise action on those that make the most difference to exporters. To boost our capacity to lead export promotion, investment and trade policy overseas, we will create a new network of Trade Commissioners to head 9 regions overseas. These regional Commissioners will add renewed focus and efficiency to our trade and investment efforts.

3.4 Deepening trade links and promoting standards

After we leave the EU, the UK intends to pursue new trade negotiations to secure greater access to overseas markets for UK goods exports as well as push for greater liberalisation of global services, investment and procurement markets, and seek ambitious digital trade packages including provisions supporting cross-border data flows, underpinned by appropriate domestic data protection frameworks.

The government is fully committed to ensuring the maintenance of high standards of consumer, worker and environmental protection in trade agreements. High standards and high quality are what our domestic and global customers demand, and that is what we should provide. Our standards can also ensure that consumers are able to have confidence in choosing products which conform to UK values, whatever their budget.

Trade agreements with single countries or groups of countries can promote and support labour protections, the environment, human rights, anti-corruption, animal welfare and other important factors which support sustainable trade and development across the world. We want to ensure economic growth, development and environmental protection go hand in hand, and it is in everyone’s interest to avoid any ‘race to the bottom’. We will have the opportunity to promote our values around the globe in the areas that are of greatest importance to us as a United Kingdom.

Until we have left the EU, the UK remains a full member of the EU and all the rights and obligations of EU membership remain in force. As we leave the EU, in line with our WTO commitments, the government will continue to maintain our high level of protections of intellectual property, consumers, the environment, and employees. We will also ensure we protect our ability to maintain control of the provision of public services, like the NHS, in new trade agreements.

We will continue to operate a robust and efficient export licensing regime for military, dual-use and other controlled items to ensure the UK meets its international obligations and commitments in the field of arms control and non-proliferation. In addition, we will put in place arrangements to enable us to operate an independent trade sanctions regime to support our wider foreign policy and national security goals.

4. Supporting developing countries to reduce poverty

The UK government has a long-standing commitment to support developing countries to reduce poverty through trade. The government will continue to deliver improved support in the future by helping those developing countries break down the barriers to trade. This will help them to continue to benefit from trade by growing their economies, increasing incomes and reducing poverty. Helping to build developing countries’ prosperity creates the conditions that allow commerce to flourish and in doing so, opens up opportunities for UK business in future markets.

One important way in which trade can support developing countries is providing preferential access for them, where generally applicable tariffs are in place. Easier access to the markets of developed countries provides vital opportunities for the world’s poorest countries to help grow their economies and reduce poverty, whilst UK business and consumers rely on these relationships for lower cost goods and greater choice of products.

As we leave the EU, we recognise the need for a smooth transition not only for the UK but also for developing countries. It is therefore important that the UK is ready to put in place a trade preferences scheme, which will, as a minimum, provide the same level of access as the current EU trade preference scheme. This will ensure that the world’s poorest countries can still benefit from duty-free access to UK markets, and that other developing countries across the globe can continue to export to the UK accordingly.

Unilateral trade preferences are schemes where WTO members that apply generally applicable tariffs offer non-reciprocal reductions in those tariffs to less prosperous developing countries. These trading arrangements set out which developing countries are eligible, what products are included, the preferential tariff rates they enjoy and the rules for operating the scheme. Often different tiers of preferential tariff will be applied to countries based on criteria such as levels of development so that less prosperous countries can receive better access. WTO rules limit such schemes to developing countries and require objective criteria for granting preferences.

The UK is currently part of the following EU arrangements, which offer preferential access to UK markets for developing countries:

- duty-free-quota-free access for 49 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) on all goods other than arms and ammunition (the ‘Everything But Arms’ scheme, or EBA)

- for the next tier of developing countries, classed as Lower Middle Income, the EU offers a mix of reductions and full removal of tariffs on around two-thirds of tariff lines (Generalised Scheme of Preferences, or standard GSP, for 13 countries)

- an enhanced tier for economically vulnerable countries that are implementing 27 international conventions on human and labour rights, environment and good governance; the two-thirds of tariff lines covered by GSP are reduced to zero (GSP+ for 9 countries)

- furthermore, the EU has been negotiating reciprocal, but asymmetrical, Economic Partnership Agreements with groups of developing countries in Africa, Caribbean and the Pacific (ACP). These allow participants to gain duty-free-quota-free access to the EU market in return for gradual and partial opening of ACP markets. They aim to promote increased trade and investment by putting our trading relationship on a more equitable, mature and business-like footing, supporting sustainable growth and poverty reduction

Many developed countries operate a preference scheme offering developing countries enhanced access to their markets. These trading opportunities help to grow economies, raise incomes and reduce poverty across the globe, helping countries to be less dependent on aid. As a result these countries are more likely to become trading partners of the future. Preferences are also important for UK businesses, particularly in the clothing, food, and retail sectors. In 2015, total UK imports from preference receiving countries were around £20 billion, of which over £8 billion attracted preferential tariffs under GSP. Preferences support UK supply chains, and consumers can benefit from cheaper prices on a wider range of products.

The UK remains committed to ensuring developing countries can reduce poverty through trading opportunities. As we leave the EU, we will maintain current access for the world’s LDCs to UK markets and aim to maintain the preferential access of other (non-LDC) developing countries. This means we will establish a UK unilateral trade preferences scheme to support economic and sustainable development in developing countries. This will include those countries currently benefitting from the EU’s GSP, including beneficiaries of the EBA, standard GSP and GSP+ tiers. We will also seek to replicate existing EPAs (in line with other EU-third country FTAs) as we prepare to leave the EU.

Our first priority is to deliver continuity in our trading arrangements with developing countries as we leave the EU. This is vital to maintain existing supply chains. Without these trading arrangements, clothing, for example, from some of the poorest countries could face tariffs of over 10% which could prevent these countries from trading effectively, and result in costs being passed on to UK consumers through higher prices at the till.

The overarching objective will be supporting economic and sustainable development in developing countries and the scheme will operate within WTO rules. We will legislate to ensure that our commitment to provide LDCs with duty-free-quota-free access to the UK market is maintained into the future. Our focus will be on those countries most in need of assistance in integrating into the global trading system and we will be clear about the criteria for eligibility to the scheme.

We are seeking views on the design of an ambitious future UK unilateral trade preference scheme, in particular:

- what elements should a UK unilateral trade preference scheme include to maximise the development impact?

- what aspects are most important for businesses exporting and importing under a trade preference scheme?

- what complementary measures can the UK offer to maximise the benefits of trade arrangements with developing countries?

Please send responses by 6 November to stakeholder.engagement@trade.gov.uk.

We will also build on our track-record as a champion of trade and development by offering a fully integrated trade and development package which strengthens support to developing countries. As well as looking to enhance market access for developing countries, our aid spending will continue to provide support and expert advice to help break down barriers to trade and promote investment so that developing countries can take better advantage of these trade arrangements. This work will consider labour protections, the environment, human rights and other factors which support sustainable development. The Department for International Trade will continue to work closely with the Department for International Development on our future trade and development policy.

5. Ensuring a level playing field

Ensuring a level playing field – a UK approach to trade remedies and trade disputes

Free trade does not mean trade without rules. To operate an independent trade policy, we will need to put in place a trade remedies framework. As an important part of a rounded trade policy, a trade remedies framework is designed to protect domestic industry against unfair and injurious trade practices, or unexpected surges in imports by allowing for measures (usually a duty) to be placed on imports of specific products. Consistent with our WTO obligations, the UK’s framework will be implemented by a new mechanism to investigate cases and propose measures that offer proportionate protections for our producers. In preparation for this, we also need to identify existing EU measures that are essential to UK business and will need to be carried forward. We will shortly be issuing a call for evidence as a first step towards identifying which existing trade remedies measures have a UK interest.

In addition, the WTO’s existing trade dispute settlement mechanism aims to resolve trade conflicts between countries and, by underscoring the rule of law, makes the international trading system more predictable and secure. The European Commission currently manages trade disputes on our and other member states’ behalf. By the time we leave the EU, we will ensure we are ready to act independently to protect UK interests should our trading partners fail to meet their international obligations and to defend any disputes brought against the UK.

5.1 Trade remedies

The UK is a strong supporter of free and fair trade. However, if a particular domestic industry suffers harm as a result of distortions of international trade (including through state-assisted subsidies and dumping), trade remedy measures can be used as a safety valve to ensure fair trade. Trade remedy measures form an important part of a rounded trade policy and as a result many WTO members have a trade remedies framework. The 3 types of trade remedies are set out in WTO agreements[footnote 31] and are known as anti-dumping, anti-subsidy (or countervailing) measures and safeguards.

The overall economic case for trade remedies needs to be considered objectively on a case by case basis. Trade remedy measures can increase the cost of affected products for user industries, and consumers, as well as the competitiveness of both user and producer industries. Therefore, it is important that measures are used judiciously and proportionately to tackle unfair trade, ensuring fair competition and addressing the injury caused to domestic producers, whilst also taking appropriate account of impacts on users and consumers and the wider trade agenda.

Trade remedies are currently an EU competence. Investigations, decisions and monitoring of trade remedy measures are performed by the European Commission on behalf of all EU member states. As the UK leaves the EU, we will need to put in place an independent UK trade remedy framework to be implemented by a new mechanism to investigate cases and propose measures. This trade remedies framework must continue to be compatible with the clear standards and requirements set out by the WTO and support our approach to trade liberalisation.

The UK’s trade remedies framework will be designed on the following principles:

Impartiality – we will develop a UK trade remedies framework that will earn the respect of our trading partners and domestic stakeholders by being impartial and objective. We will achieve this through:

- creating a new, independent, trade remedies investigating authority as a new arm’s length body that will investigate trade remedies cases and make recommendations on the basis of clear economic criteria. The new UK trade remedies investigating function will need to be operational by the time we leave the EU. This will enable it to take on new investigations and reviews of existing cases.

- ensuring that the investigation process is as transparent, objective and efficient as possible

- providing a route for interested parties to appeal decisions made by the investigating authority

Proportionality – we will ensure that the UK’s trade remedies framework is used judiciously and proportionately. Decisions will be based on clear evidence, targeted at addressing the injury caused, and take into account the interests of domestic producers and regional impacts, as well as those of other interested parties, such as user industries and consumers. We will achieve this through:

- Applying an economic interest test as part of the trade remedies investigation, prior to the application of provisional or definitive measures. The detail of how this test works in practice will be informed by internal and external analysis and finalised later in the year when it will be set out in secondary legislation or guidance. We have been engaging with stakeholders to get their views and are committed to continuing that process.

- Applying a UK-specific threshold for initiating cases in addition to the basic WTO threshold which specifies the minimum market share required for the domestic industry to bring an investigation. Other countries’ trade remedy regimes often have a method of filtering cases at the initiation stage to avoid investing resources in investigations which are very unlikely to result in measures. Not all systems are clear about the filtering process but the UK would like to clarify this approach in secondary legislation so the system is more transparent and more predictable for business. We are in the process of conducting further work on the detail of this proposal, including what the threshold should be, and have been engaging with stakeholders to get their views on this, and are committed to continuing that process.

- Applying duties based on the level of injury caused by the dumping or subsidy, as identified during the investigation process. The methodology for calculating injury will be informed by internal and external analysis and we have been sharing our thinking with stakeholders as the work develops, and are committed to continuing that process.

Efficiency – we will ensure that cases are investigated swiftly and effectively, avoiding unnecessary burdens on complainants as well as the subjects of the complaint, and we will ensure the effectiveness of trade remedy measures. We will achieve this through:

- applying provisional measures according to WTO rules when they are needed to protect the domestic industry during an investigation, so that measures can be in place as quickly as possible

- developing a digital service to support the investigations process

- introducing measures to tackle attempts to circumvent or absorb trade remedies through specific review processes

- legislating to allow the use of undertakings[footnote 33] but carefully examining the circumstances in which undertakings should be sought and accepted in lieu of duties

Transparency – balancing the need to protect commercially confidential data whilst ensuring that relevant information about cases is accessible to interested parties, and that there is accountability for decision-making. We will achieve this through:

- making the system and the process as transparent as possible, within the boundaries set in the WTO agreements to protect commercial confidentiality, so that parties to investigations are able to make their case effectively

- ensuring that transparency arrangements do not create an unreasonable burden on the businesses that take part in the process

Engaging our stakeholders

Many industrial sectors are not well versed in trade remedies policy, but there are a small number of sectors that have been impacted by dumped or subsidised imports that have a high level of expertise in the area. We know from the stakeholder engagement we have already conducted that, when it comes to the future of the trade remedies framework, UK companies are looking for certainty, continuity and as much notice as possible for any significant changes that might directly impact them.

The Department for International Trade has an ongoing programme of engagement with all relevant stakeholders including representatives from producer and user industries, as well as consumer and retail groups, to understand their specific concerns and to provide an opportunity for them to feed in to the detailed design of the system as we develop secondary legislation. This engagement takes the form of a series of roundtables and bilateral meetings. We are interested in comments and views on all aspects of the trade remedy framework.

The department invites any stakeholders who have an interest in trade remedies and are not yet involved in this work to contact us at stakeholder.engagement@trade.gov.uk for further details.

Transferring existing EU trade remedy measures

The EU currently has over 100 measures in place on imported goods originating from 25 different non-EU countries. Based on European Commission estimates, this represents only around 0.5% of all imports into the EU, but from the point of view of the domestic producers of those products these measures are vital and ensure fair competition.

Once the UK has left the EU, and taking into account any time-limited implementation period, UK businesses will no longer be able to make a request to the European Commission to investigate claims of dumping or subsidy in the UK. If no action is taken to transition existing trade remedy measures they will, with immediate effect, no longer apply to products arriving into the UK.

Without action, this could have serious effects on certain UK industries including those in the steel, ceramics and chemicals sectors. In order to provide certainty to business and ensure continuity, we will seek to effectively continue the existing trade remedies measures which matter to UK business, and which meet WTO requirements around the level of domestic production. We will review them to ensure that they are tailored to the needs of the UK economy.

As a first step in this process we will shortly be issuing a call for evidence in order to identify which existing EU trade remedy measures are relevant to UK companies. Once we have this information we will be able to assess those measures. We will set out our approach for transitioning existing measures in more detail in the Call for Evidence and, recognising that participating in trade remedy processes can be resource intensive for business, we will ensure that we allow adequate notice and time to collect any further information that we may require.

5.2 Conducting trade disputes

The WTO has a dispute settlement mechanism for resolving trade conflicts between member governments. The purpose is to ensure that the multilateral rules-based system governing international trade is effective by providing member governments with a means of enforcement when another member breaches its obligations. By underscoring the rule of law, dispute settlement makes the trading system more predictable and secure. In addition, as the UK agrees new preferential trade agreements with specific trading partners, it will need to be prepared to enforce the obligations of those agreements by way of dispute settlement, including by using the dispute mechanisms provided for in those agreements.