Improving Lives: Helping Workless Families Indicators 2020: Data for 2005 to 2019

Published 26 March 2020

Contact Details

helpingworklessfamilies@dwp.gsi.gov.uk

DWP Press Office: 0203 267 5129

Feedback is welcome

What you need to know

Despite record levels of employment, for some families, worklessness, not employment, is the norm. These families face huge barriers to entering work and taking advantage of the opportunities that employment affords. Worklessness damages lives. It reduces families’ income, damages families’ resilience, health, stability, and can have a long-term impact on their children’s development. When problems such as these combine and fuel each other, families edge further and further away from the benefits of work, and children are more likely to repeat the poor outcomes of their parents.

There are 9 indicators and underlying measures used to track national progress in tackling the disadvantages that affect families and children’s outcomes:

1. Parental Worklessness

2. Parental Conflict

3. Poor Parental Mental Health

4. Parental Drug and Alcohol Dependency

5. Problem Debt

6. Homelessness

7. Early Years

8. Educational Attainment

9. Youth Employment

The government has a statutory duty to report data annually to Parliament on 2 of the 9 indicators for England only:

1. Parental Worklessness

a. The proportion of children living in workless households

b. The proportion of children living in long-term workless households

2. Educational attainment at Key Stage 4

Read the annual update on these indicators

Indicator 1: Parental Worklessness

Workless households are households where no one aged 16 years or over is in employment. These members may be unemployed or economically inactive. Economically inactive members may be unavailable to work because of family commitments, retirement or study, or sickness or disability.

A long-term workless household is a workless household, as defined above who have been workless for at least 12 months or have never worked (in a paid job). A long-term workless household does not necessarily imply that adults within them have been long-term unemployed. Some adults may have been out of work for 12 months or more, but had periods of inactivity such as looking after family or illness during that time.

9% of all children were living in workless households between October and December 2019

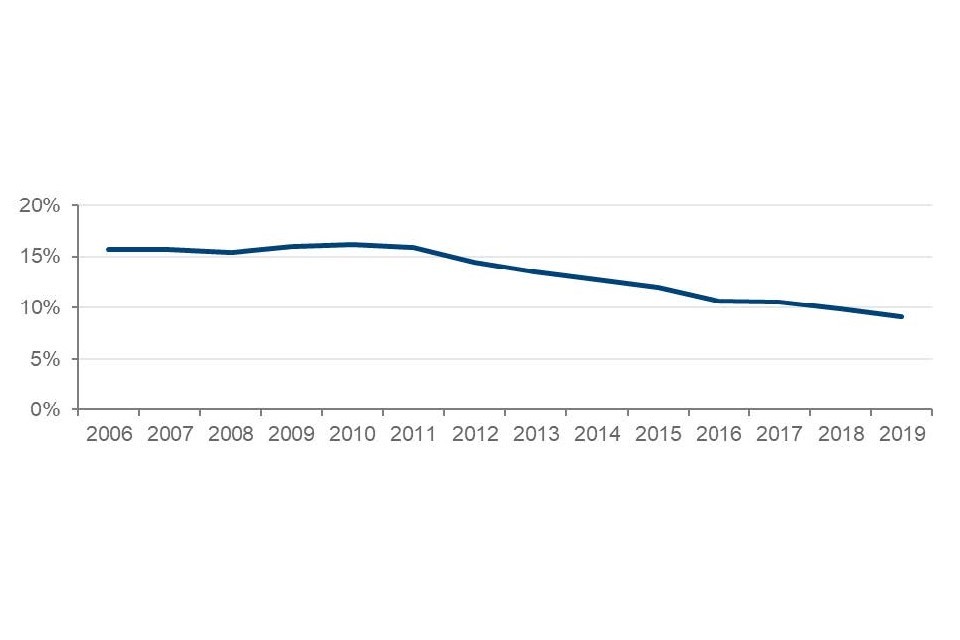

Proportion of children living in workless households (UK), 2006 to 2019

9% of children were living in workless households in the fourth quarter of 2019. This has reduced from a peak of 16% in 2010.

Source: Labour Force Survey, October to December 2019

9% of all children (around 1.2 million children) were living in workless households in the fourth quarter of 2019. This has reduced by 75,000 children from the previous year.

The percentage of children in workless households is from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which samples around 100,000 people each quarter. To avoid seasonal fluctuations in quarter-on-quarter data results from October to December are compared each year.

8% of all children had been living in workless households for at least 12 months in 2018

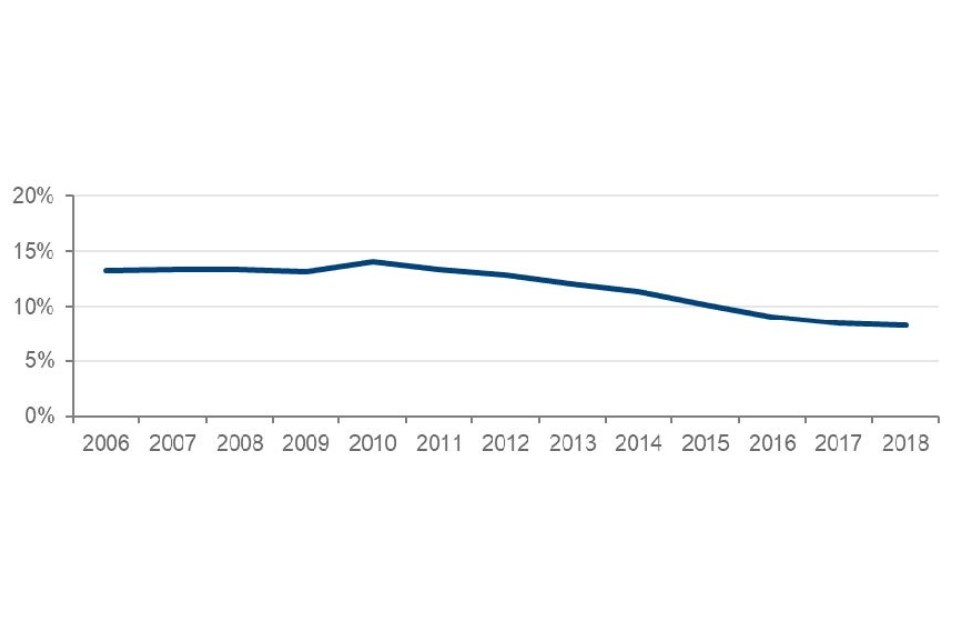

Proportion of children living in long-term workless households (UK), 2006 to 2018

8% of children were living in long term workless households between 2017 and 2018. This has gradually reduced sinced 2010.

Source: Annual Population Survey, 2018

8% of all children (around 1 million children) were living in long-term workless households in 2018. This is 11,000 fewer children than the previous year.

The percentage of children in long-term workless households is from the Annual Population Survey (APS), which samples around 300,000 people per year. The survey combines additional interviews with interviews from the LFS.

More information

Working and workless households in the UK: October to December 2019

Children living in long-term workless households in the UK: 2018

Indicator 2: Parental Conflict

The proportion of children living in separated families who see their non-resident parents regularly has not been updated this year as the statistic has been suspended. A change in the coverage of source data means that the available data on separated families does not represent the whole separated parent family population for the period 2017-2018. The separated families measure will be available again for the period 2019-20.

The parental conflict measures have been developed using Understanding Society survey data. The Understanding Society survey interviews up to 40,000 households across the UK each year. Households are asked questions relating to relationship distress once every two years.

Experiencing relationship distress is defined as when either parent in a couple-parent family states that most or all of the time they consider divorce, regret living together, quarrel, or get on each other’s nerves (in response to questions asking about their relationship with their partner).

Regular contact with the non-resident parent is defined as when the resident parent states that the child ‘usually sees’ the non-resident parent ‘at least fortnightly’ during term time. Regular contact between children and their parents is a positive outcome and serves as a proxy measure for reasonable quality inter-parental relationships in separated families.

12% of children in couple-parent families were living with at least one parent reporting relationship distress

52% of children in separated families saw their non-resident parent at least fortnightly – Statistic suspended

Proportion of children in couple-parent families reporting relationship distress (UK), 2011 to 2018

| Period | Proportion |

|---|---|

| 2011 to 2012 | 13% |

| 2013 to 2014 | 12% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 11% |

| 2017 to 2018 | 12% |

Source: Understanding Society survey, 2011-2018

Proportion of children in living in separated families who see their non-resident parents regularly (UK), 2013 to 2016

| Period | Proportion |

|---|---|

| 2013 to 2014 | 53% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 52% |

Source: Understanding Society survey, 2011-2018

This publication uses cross-sectional analysis i.e. it uses survey results where children are present in any of the surveys where the relationship and regularity of contact questions have been asked. This is different to the methodology used in the original Improving Lives Publication (2017) and means that the figures cannot be compared.

More information

Parental conflict indicator 2011/12 to 2017/18

Indicator 3: Poor Parental Mental Health

Poor Parental Mental Health is measured using the Understanding Society survey, which captures information from up to 40,000 households across the UK each year. The questions come from the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), which is the most widely used screening tool for common mental disorders.

Twelve questions are asked about an individual’s self-confidence, worries and sleep amongst other things over the past few weeks. The questions have two negative options (where the respondent feels worse than usual) and two positive options (where the respondent feels the same or better than usual). Scores of one are given to negative responses and zero to positive responses. Scoring four or more classifies the person as reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression.

This is considered a better measure of poor mental health than asking the respondent if they have been diagnosed with depression or anxiety, as asking the respondent directly is likely to under-represent the level of poor mental health due to under-diagnosis and under-reporting.

The proportion of children living with at least one parent reporting symptoms of emotional distress was 30% in 2017-18

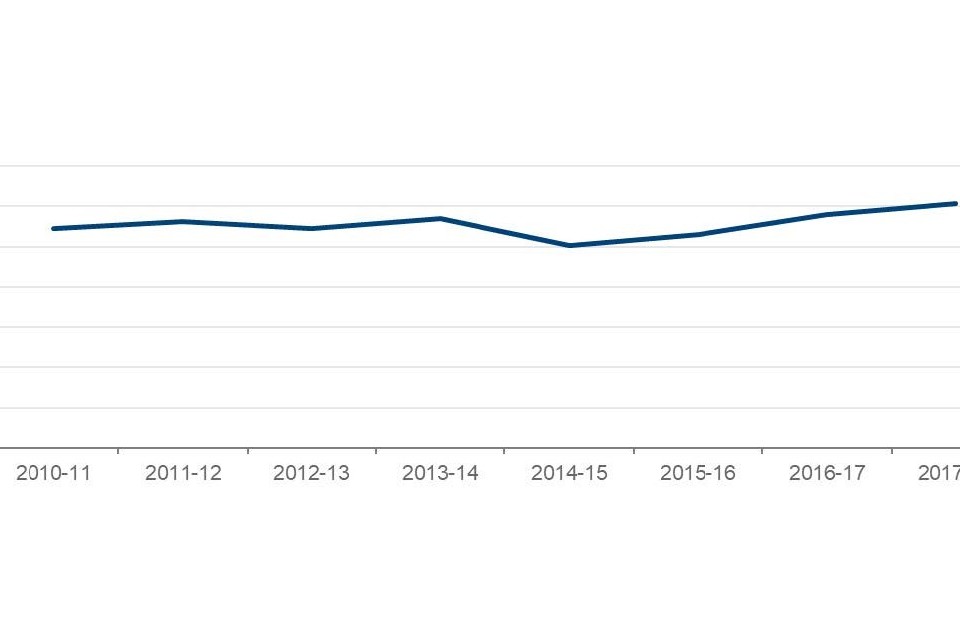

Proportion of children living with at least one parent reporting symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (UK), 2010 to 2018

The proportion of children living with at least one parent reporting symptoms of anxiety and/or depression was 30%, this is the highest figure since 2010-11.

Source: Understanding Society survey, 2010-18

The proportion of children living with at least one parent reporting symptoms of emotional distress has increased each year from 2014-15. The latest figure of 30% in 2017-18 is the highest since 2010-11.

More information

Children living with parents in emotional distress: 2019 update

Indicator 4: Parental Drug and Alcohol Dependency

Parents are defined as individuals aged 18 and over that have children (aged under 18) living with them. The data on parents involved in treatment also includes individuals who are pregnant.

In 2017-18 around 117,867 parents were estimated to be dependent on alcohol in England

The number of parents who are opiate users or dependent on alcohol (England), 2010 to 2018

| Period | Alcohol | Opiates |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 to 2011 | 118,000 | - |

| 2011 to 2012 | 117,000 | 82,000 |

| 2012 to 2013 | 117,000 | - |

| 2013 to 2014 | 121,000 | - |

| 2014 to 2015 | 120,000 | 76,000 |

| 2015 to 2016 | 120,000 | - |

| 2016 to 2017 | 119,000 | - |

| 2017 to 2018 | 118,000 | - |

Source: Public Health England

Over the last seven years, the number of alcohol-dependent parents has remained largely stable. It decreased slightly from 118,700 in 2016-17 to 117,867 in 2017-18. The number of parents who are opiate users has not been updated since 2014-15.

The estimates of alcohol dependency are carried out by Sheffield University with support from Public Health England. They use data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Study (APMS), Office for National Statistics census information and data on hospital admissions. Opiate dependency uses data from the Police National Computer, probation and prison treatment data and data from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System. They are produced by Liverpool John Moores University and Manchester University with support from Public Health England.

In 2016-19 51% of parents with alcohol dependency and 16% of opiate using parents who entered treatment, completed it and did not return for more treatment within the three years

Proportion of alcohol dependent or opiate using parents who have entered and completed treatment within the last three years (England), 2008 to 2019

| Period | Alcohol | Opiates |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 to 2011 | 41 | 14 |

| 2009 to 2012 | 45 | 16 |

| 2010 to 2013 | 48 | 17 |

| 2011 to 2014 | 50 | 16 |

| 2012 to 2015 | 51 | 16 |

| 2013 to 2016 | 51 | 16 |

| 2014 to 2017 | 51 | 16 |

| 2015 to 2018 | 52 | 16 |

| 2016 to 2019 | 51 | 16 |

Source: Public Health England

The proportion of alcohol-dependent parents completing treatment increased from 48% in 2010-13 to 51% in 2016-19. The percentage of parents completing treatment for opiate use has remained at 16% since 2011-14.

The proportion of alcohol-dependent parents or opiate using parents completing treatment uses information collected through the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System, which is analysed by Public Health England. Parents are counted if they have entered, completed and not returned for treatment within three years. Opiate users must not be receiving any substitute medication at the time of leaving treatment.

More information

Substance misuse treatment for adults: statistics 2018 to 2019

Indicator 5: Problem Debt

A household is considered as being in problem debt if it falls into any of these groups:

- At least one adult reports falling behind with bills or credit commitments and the household’s debt repayments are at least 25% of the household’s net monthly income.

- At least one adult reports falling behind with bills or credit commitments and at least one adult is currently in two or more consecutive months’ arrears on bills or credit commitments.

- At least one adult considers debt a heavy burden and the household’s debt represents at least 20% of the household’s net annual income.

Persistent problem debt is where children are in a household in problem debt in two consecutive waves of the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS).

The most recent data shows 2% (around 230,000) of all children in Great Britain were living in households in persistent problem debt

Proportion of all children living in households in persistent problem debt (Great Britain), 2010 to 2018

| Period | Proportion |

|---|---|

| 2010 to 2011 and 2012 to 2013 | 4.6% |

| 2011 to 2012 and 2013 to 2014 | 6.2% |

| 2012 to 2013 and 2014 to 2015 | 3.8% |

| 2013 to 2014 and 2015 to 2016 | 4.0% |

| 2014 to 2015 and 2016 to 2017 | 3.9% |

| 2015 to 2016 and 2017 to 2018 | 2.0% |

Source: Wealth and Assets Survey (Great Britain)

The proportion of children living in households in persistent problem debt fell to 2% from 3.9% in the most recent two-year period. It is still well below its peak of 6.2% in 2011-12 and 2013-14.

Proportion of all children living in households in problem debt (Great Britain), 2010 to 2018

| Period | Proportion |

|---|---|

| 2010 to 2011 | 12.6% |

| 2011 to 2012 | 14.3% |

| 2012 to 2013 | 11.3% |

| 2013 to 2014 | 10.9% |

| 2014 to 2015 | 9.9% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 9.7% |

| 2016 to 2017 | 7.8% |

| 2017 to 2018 | 7.8% |

Source: Wealth and Assets Survey (Great Britain)

The proportion of children living in households in problem debt is not part of the Problem Debt Indicator but provides evidence to support the measure. 7.8% of children were living in households in problem debt in 2017-2018.

More information

Problem debt, Great Britain: July 2010 to June 2016 and April 2014 to March 2018

Indicator 6: Homelessness

The term ‘homelessness’ does not only apply to people ‘sleeping rough’. For this indicator, homelessness is statutory homelessness, where a local authority has accepted a homeless duty for a household.

A homelessness duty is where a local authority is satisfied that the household is unintentionally homeless, eligible for assistance and is in a specified priority need group e.g. they have dependent children. Suitable accommodation must be made available by the local authority when there is a homelessness duty. This can involve placing the household in temporary accommodation until a settled housing solution becomes available or until some other circumstance ends the duty.

Around 9 in every 1,000 households in England with dependent children (around 62,000 households) were living in temporary accommodation at the end of June 2019

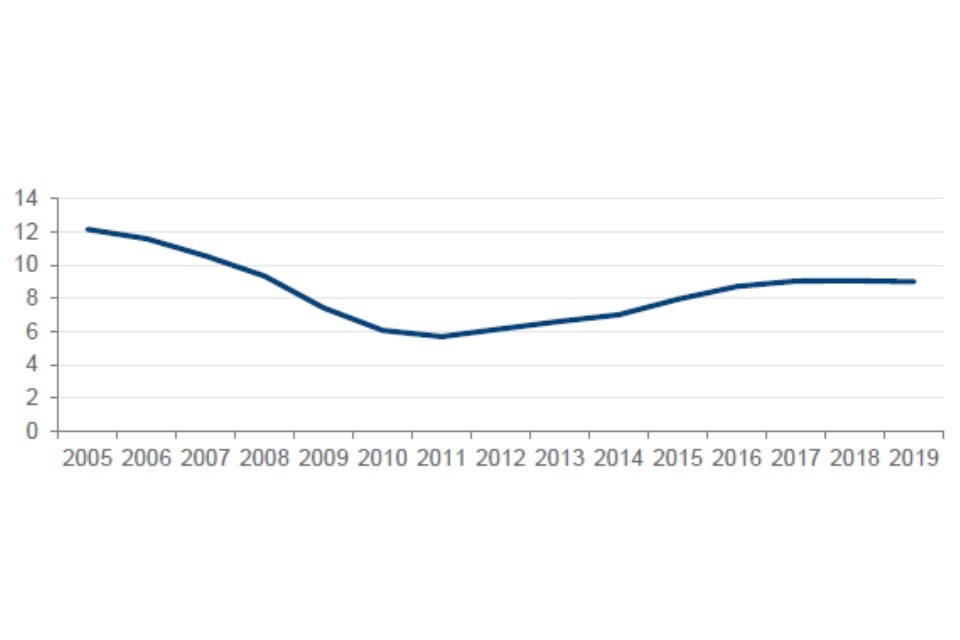

Households with dependent children living in temporary accommodation per 1,000 households (England), 2005 to 2019

9 in every 1,000 (62,000) households were living in temporary accommodation with children at the end of June 2019. This is below the maximum of 12 in every 1,000 (73,000) households at the end of June 2005.

Source: Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government Homelessness Statistics and Household Projections

9 in every 1,000 (62,000) households were living in temporary accommodation with children at the end of June 2019. This is below the maximum of 12 in every 1,000 (73,000) households at the end of June 2005.

The number of households with dependent children living in temporary accommodation per 1,000 households combines statistics on dependent children in temporary accommodation and projections of the number of households with dependent children from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Information on the number of households in temporary accommodation is collected from local authorities on the last day of each quarter.

More information:

2014-based household projections: detailed data for modelling and analytical purposes

Indicator 7: Early Years

The Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP) assesses children in state-funded early years’ education against seventeen early learning goals. Teachers assess children through classroom observations during the academic year in which they turn five. A “good level of development” is achieving at least the expected level in communication and language, literacy, mathematics and physical, personal, social and emotional development.

Comparisons cannot be made with EYFSP results before 2013 as the EYFSP was changed in 2012. with greater emphasis being placed on communication and language and physical, personal, social and emotional development.

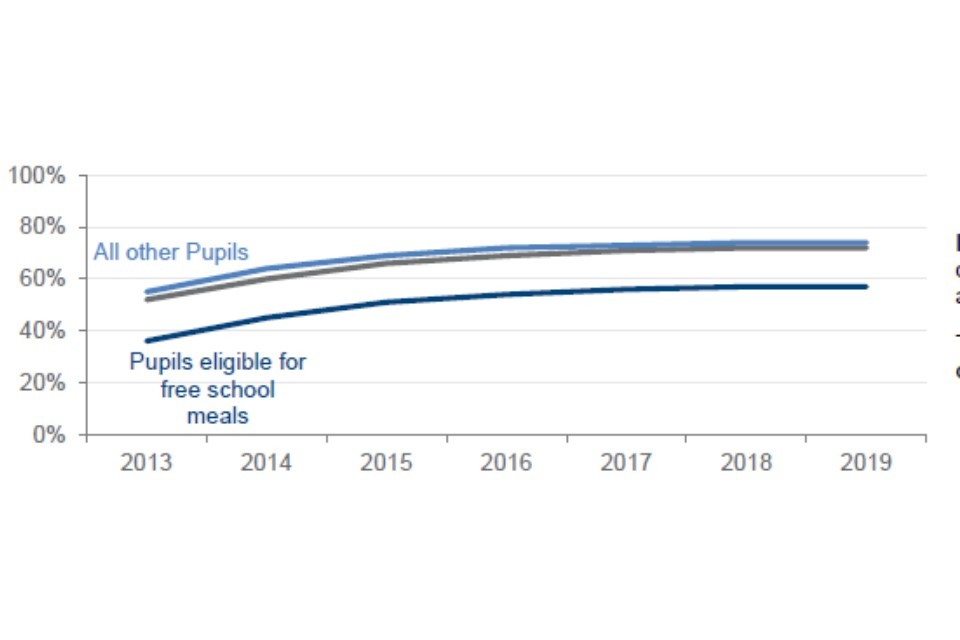

57% of pupils eligible for free school meals in 2019 achieved a good level of development on the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile

Proportion of children achieving a good level of development on the EYFSP at age five (England), 2013 to 2019

In 2019, 57% of pupils eligible for free school meals achieved a good level of development on the EYFSP, this compares to 74% of all other pupils and 72% of all pupils.

In 2019, 57% of pupils eligible for free school meals achieved a good level of development on the EYFSP, this compares to 74% of all other pupils and 72% of all pupils.

The percentage of pupils in all three groups achieving a good level of development continues to increase each year.

Attainment gap for “good level of development” between pupils eligible for free school meals and all other pupils (England), 2013 to 2019

| Year | Attainment gap |

|---|---|

| 2013 | 19.0 |

| 2014 | 18.9 |

| 2015 | 17.7 |

| 2016 | 17.3 |

| 2017 | 17.0 |

| 2018 | 17.3 |

| 2019 | 17.8 |

Source: National pupil database

The “good level of development” attainment gap between pupils eligible for free school meals and other pupils is not part of the Early Years indicator but provides evidence to support the measure. It is calculated from the difference in the percentage of pupils achieving a “good level of development” who are eligible for free school meals and the percentage of all other pupils achieving the same.

In 2019, the “good level of development” attainment gap between pupils eligible for free school meals and all other pupils increased slightly to 17.8 from the 2018 figure of 17.3.

More information

Early years foundation stage profile results: 2018 to 2019

Indicator 8: Educational Attainment

31% of pupils at the end of Key Stage 2 and 26.5% of pupils at the end of Key Stage 4 were classified disadvantaged in state funded schools in 2019. Pupils are defined as disadvantaged if they have been eligible for free school meals in the previous six years, they have been looked after for at least one day during the year or they have ceased to be looked after by a local authority in England because of adoption, a special guardianship order, a child arrangements order or a residence order.

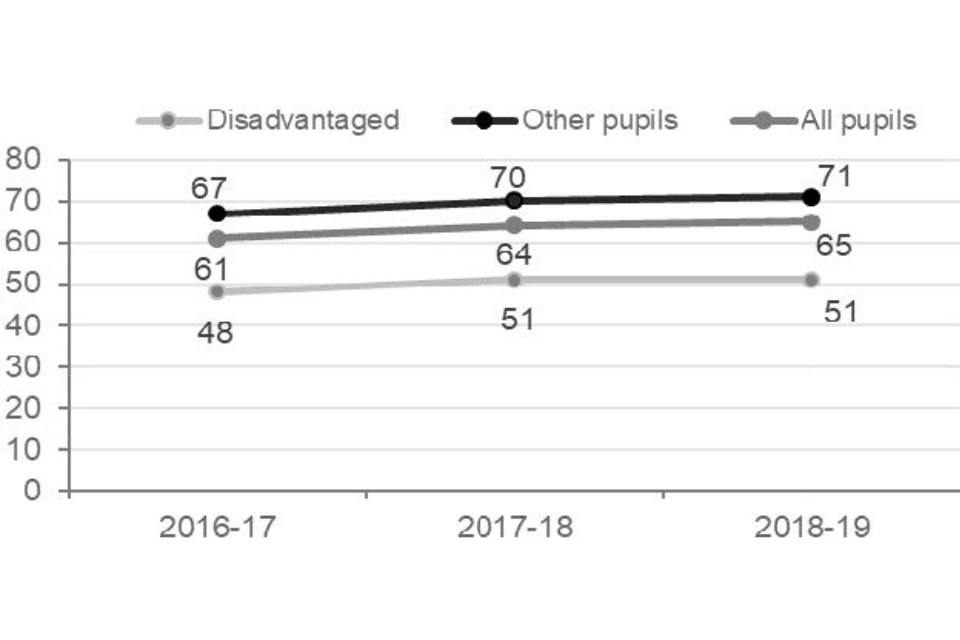

Attainment at Key Stage 2 is the proportion of pupils reaching the expected standard in reading, writing and maths

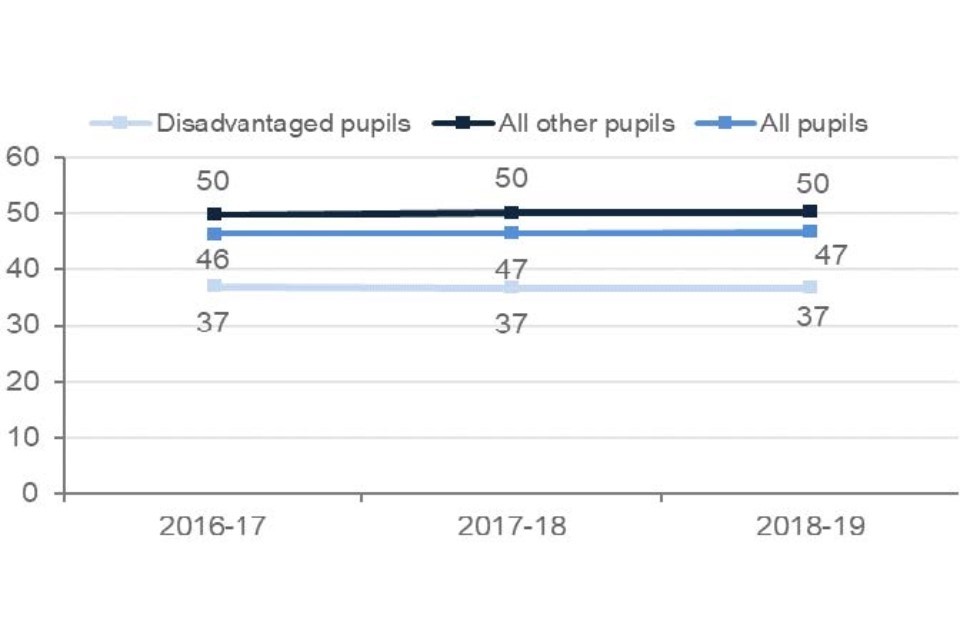

Attainment at Key Stage 4 has changed in this publication due to the continuing reforms of GCSEs. Attainment at Key Stage 4 is now the average “attainment 8” score per pupil in state-funded schools. This measures attainment across eight subjects rather than just Maths, English language and English literature.

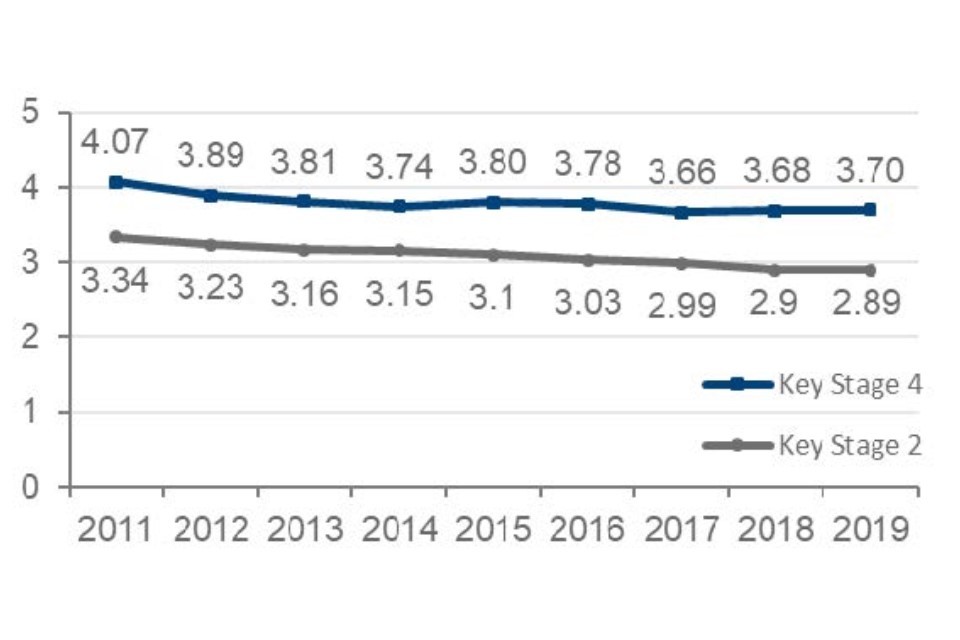

The Disadvantage Attainment Gap Index for Key Stage 2 and 4 is not part of the Educational Attainment indicator but provides evidence to support the measures. It shows if disadvantaged pupils are catching up or getting left behind. A disadvantage attainment gap of zero shows that disadvantaged pupils are performing as well as other pupils. The maximum possible gap is 10 or -10 if disadvantaged pupils perform better than other pupils.

The most recent data shows:

At Key Stage 2:

51% of disadvantaged pupils achieved the expected standard in reading, writing and maths

71% of other pupils achieved the expected standard in reading, writing and maths

65% of all pupils achieved the expected standard in reading, writing and maths

At Key Stage 4:

The average attainment 8 score for disadvantaged pupils was 37

The average attainment 8 score for other pupils was 50

The average attainment 8 score for all pupils was 47

Attainment at Key Stage 2 (England)

The attainment at key stage 2 has remained constant in 2018-19 for the disadvantaged group, and increased by 1 percentage point for other and all pupils.

Attainment at Key Stage 4 (England)

Attainment at key stage 4 has remained constant for all three groups of pupils, at 50 for other pupils, 37 for disadvantaged pupils and 47 for all pupils.

Disadvantage Attainment Gap Index at Key Stage 2 and 4 (England), 2011 to 2019

The attainment gap index at key stage 4 was 3.7 in 2019, and 2.89 at key stage 2. These have both fallen from peaks in 2011.

Source: National pupil database and Key Stage 4 attainment data

The data is created from school census records, qualification entries, attainment data, data returns from local authorities and results collected from awarding organisations.

It includes pupils in state-funded schools who have reached the end of KS2 or KS4 in the academic year.

More information

National curriculum assessments: key stage 2, 2019 (provisional)

Key stage 4 performance, 2019 (provisional)

Measuring disadvantaged pupils’ attainment gaps over time

Indicator 9: Youth Employment

Around 11% (763,000) of young people aged 16 to 24 are not in education, employment or training

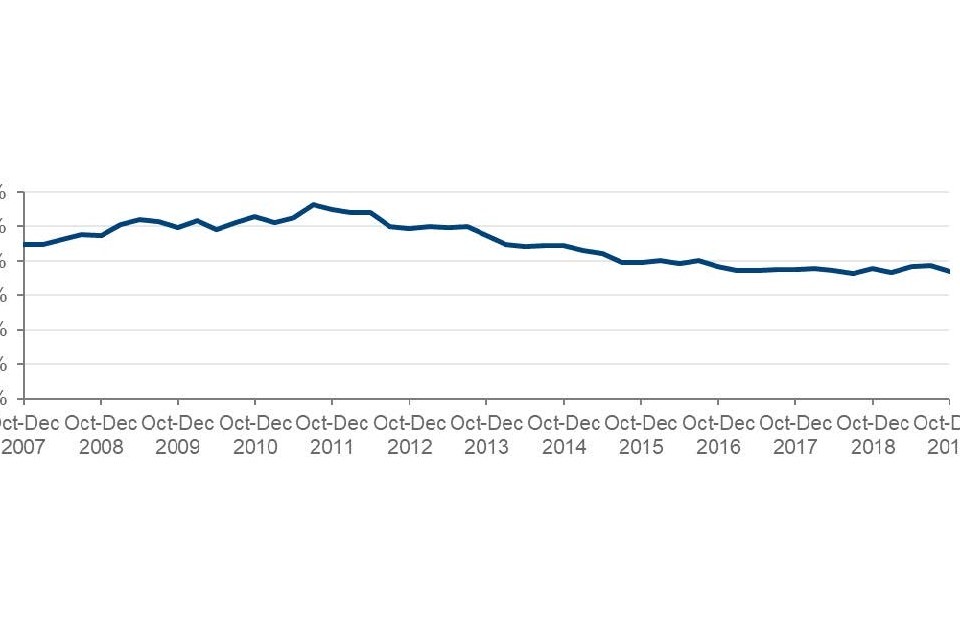

Proportion of young people (aged 16 to 24) who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) (UK), 2007 to 2019

The proportion of young people aged 16-24 not in education, employment or training was 11.1% in December 2019. This is 5.8 percentage points lower than the peak of 16.9% in July to September 2011.

Source: Labour Force Survey

The proportion of young people (aged 16 to 24) who are not in education, employment or training in October to December 2018 was 11.1%, this has decreased by 0.2 percentage points since last year. This is 5.8 percentage points lower than the peak of 16.9% in July to September 2011.

The data is from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) which samples around 100,000 people each quarter and the estimates are seasonally adjusted.

The Government increased the age to which all young people in England are required to continue in education or training, from 16 to 18 between 2013 and 2015. This will have decreased the proportion of 16 to 17 year olds who were not in education, employment or training in 2015 and early 2016.

Almost 6% of young people aged 18 to 24 haven’t been in employment or full-time education for two years

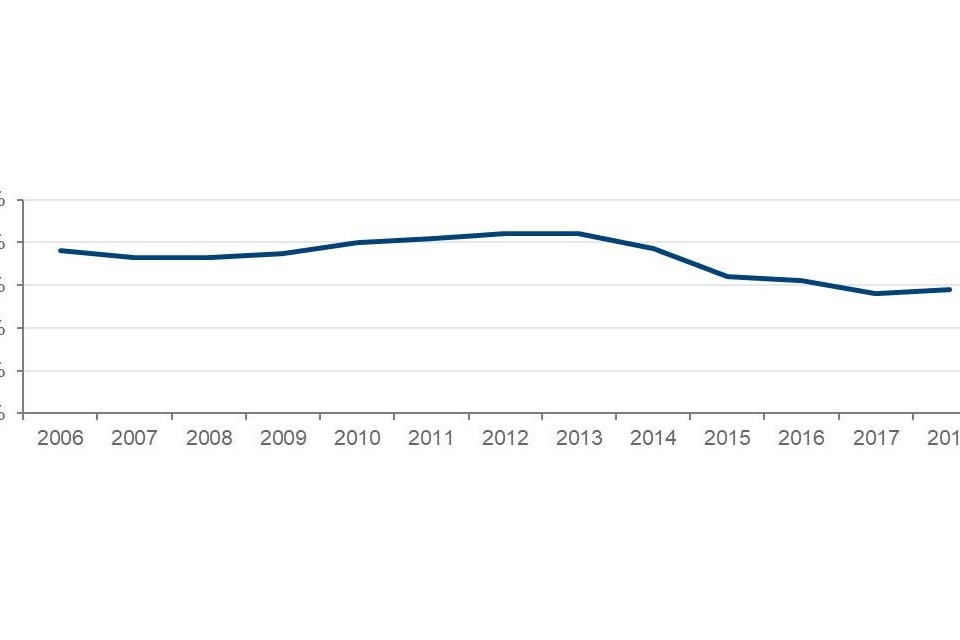

Proportion of young people aged 18 to 24 who have not been in employment or full-time education for two years or more (UK), 2006 to 2018

The proportion of young people who have not been employed or in full time education has risen by 0.2 percentage points from its lowest level in 2017 to 5.7% in 2018.

Source: Annual Population Survey

The proportion of young people (aged 18 to 24) who have not been in employment or full-time education has risen by 0.2 percentage points from its lowest level in 2017 to 5.8% in 2018.

The data is from the Annual Population Survey (APS), which samples around 300,000 people per year. The survey combines additional interviews with interviews from the LFS. A two-year threshold is used to eliminate those voluntarily spending time out of the labour market e.g. those on a gap year.

More information

Young people not in education, employment or training (NEET), UK: February 2020

Young people in long-term workless households, UK, 2006 to 2018