Final report of Charity Commission safeguarding taskforce

Published 17 October 2018

Background

In February 2018, the Charity Commission announced a suite of measures to help ensure charities, and the Commission, learned the wider lessons from safeguarding revelations involving Oxfam and other charities, and to strengthen public trust and confidence in charities.

One of these measures was the establishment of an internal taskforce with two main purposes. These were to:

- respond robustly and consistently to the significantly increased volume of serious incident reports on safeguarding matters submitted by charities to the Commission following the safeguarding revelations involving Oxfam

- undertake a ‘deep dive’ of the Commission’s serious incident reporting records dating back to April 2014, to identify any gaps in full and frank disclosure by charities and to ensure charities and the Commission had taken appropriate follow-up actions to deal with the incident reported.

In addition, the taskforce undertook detailed analysis of the reports of serious safeguarding incidents submitted by charities between February and May 2018.

The purpose of this work was to explore the nature of incidents reported and the type of charity making the report, in order to inform our understanding of risks facing charities, and in turn our approach to individual case work and the provision of guidance to charities.

This report provides a summary of the findings emerging from the work of the taskforce.

Key findings and conclusions of the work of the taskforce

Our deep dive of the Commission’s records of historic reports of serious incidents did not identify any cases where there are serious concerns about either the charity’s or the Commission’s handling at the time.

However, we found that we had not always received enough evidence that charities were learning the wider lessons from incidents, in order to help prevent similar problems from occurring in future.

Reports of serious safeguarding incidents were not always made sufficiently quickly; our guidance requires charities to report a serious incident promptly.

We have serious concerns about continued underreporting of serious incidents in charities.

We must undertake further analysis to assess whether, and if so why, certain types/ characteristics of charities where underreporting may be especially prevalent, in order to target those with regulatory advice and guidance.

New reports of safeguarding incidents

There has been a significant increase in safeguarding reports received since the start of February 2018, when there was an increased public spotlight on charities, reporting and how they handle incidents.

During the months of February and March 2018, we received three times as many reports of safeguarding incidents compared to the same period in 2017 (532 in February - March 2018, compared to 176 in February – March 2017).

Our view is this marked upturn came as a direct consequence of the public and charity sector focus on safeguarding practices in charities, and on charities’ responses to incidents when they do occur. We also consider the increase in reports resulted, in part, from the Commission’s reminder to charities in February that if there were serious incidents they should have previously reported but had not, now was the time to do so.

The initial increase has been sustained since March 2018: in total, in the period from 20 February 2018 to 30 September 2018, charities submitted 2,114 reports of serious incidents (RSIs) relating to safeguarding incidents or issues, representing 68% of the total number of reports submitted by charities in that period.

This compares to 1,580 serious incident reports about safeguarding received in the whole of 2017-18, and 1,203 received in 2016-17.

Chart 1: Number of RSI reports about safeguarding since 2016

| Year | RSIs about safeguarding |

|---|---|

| 2016 | 1,203 |

| 2017 | 1,580 |

| 2018 (20 February to 30 September) | 2,114 |

We have been clear that reporting serious incidents to the regulator and reporting criminal matters to the police is part of what trustees need to do if acting responsibly to protect those at risk of harm and ensure public trust.

Nature of safeguarding reports – further analysis

We undertook a detailed analysis of 1,228 safeguarding reports submitted to us between 1 February and 31 May. The purpose of this analysis was to better understand the nature of the incident being reported and the type of charity making the report.

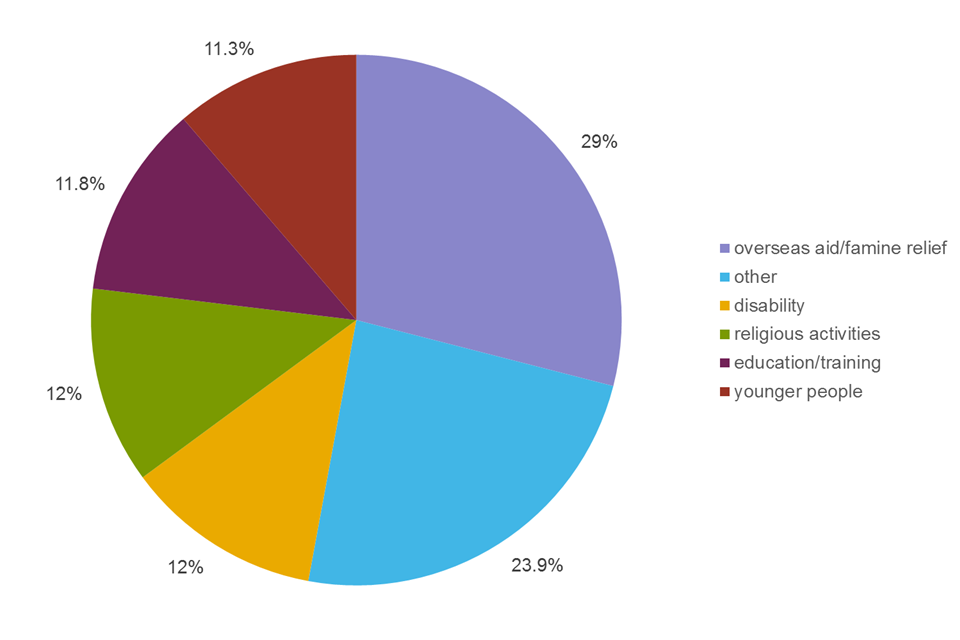

Breakdown by charity type

We were keen to look at the type of charity reporting serious incidents. We did this by looking at the primary classification or type of charity, as reported by charities themselves in their annual returns.

The top five classifications of charity that submitted safeguarding RSIs were:

- overseas aid/famine relief (366 RSIs or 29%)

- disability (151 RSIs or 12%)

- religious activities (151 RSIs or 12%)

- education/training (146 RSIs or 11.8%)

- younger people (140 RSIs or 11.3%)

Chart 2: Classifications of charity that submitted safeguarding RSIs

Classifications of charities that submitted RSIs were:

- 29% overseas aid / famine relief

- 23.9% other

- 12% disability

- 12% religious activities

- 11.8% education / training

- 11.3% younger people

We compared these figures against the overall of number of charities with respective classifications on the register as a whole. This resulted in some notable findings.

For example, only 6.7% of charities overall select the classification overseas aid/famine relief, yet charities of this type submitted nearly a third of all safeguarding RSIs in the sample. In contrast, over 52% of all registered charities select the classification education/training yet charities of this type submitted only 11.8% of all safeguarding RSIs in the sample.

There is a similar picture as regards the younger people classification – over 56% of registered charities selected that classification but only 11% of RSIs submitted came from charities of this type. (Note: Charities can have more than one classification type).

We consider that this divergence results in part from historic underreporting by certain types of charities – in other words that the sample period saw such charities ‘catching up’ by reporting matters that ought to have been reported during earlier periods.

However, we are now undertaking further analysis to get a better understanding of why some types of charities may be underreporting serious incidents compared to others.

Breakdown by incident type

The reports submitted covered a wide spectrum of incidents, in line with our serious incident reporting guidance. However, our analysis does suggest that the majority of reports related to incidents of or concerns about potential harm having come to individuals.

These covered a range of types of incident, and were not limited to alleged sexual abuse or harassment. Incidents reported included, for example, an allegation of bullying against a staff member, a road accident resulting in serious harm to a child and a service user physically attacking a volunteer.

Only 56 RSIs (approx. 4.6%) involved no individual identified as having allegedly been harmed or placed at risk of harm. For example, one report saw a charity failing to conduct DBS checks; no actual harm occurred as a result. In those reports where an individual who may have been harmed could be identified, 583 (approx. 47.5%) related to a child and 395 (approx. 32 %) to an adult.

Breakdown of abuse cases by individual responsible

In nearly 88% (1,078) of the 1,228 serious incidents submitted the alleged individual responsible was connected to the charity. There were 25 incidents (2%) where there was no such connection. In the remainder it was unclear from the initial report whether there was a connection.

Notably, a significant majority of the individuals thought to be responsible were employees (around 65 %), with volunteers making up 11.8% of the remainder. Others included trustees (26 RSIs or 2%), beneficiaries (69 RSIs or 5.6 %) and members (30 RSIs or 2.4 %).

Timeliness of reporting

The Commission’s guidance for reporting a serious incident is that the incident should be reported promptly. The only exception is for charities that make multiple reports and have an agreement to report in bulk periodically, rather than reporting each incident separately. Even excluding bulk reporting, there were 818 SIRs (65.9%) reported more than two months after the serious incident had occurred.

Multiple reporting

624 RSIs (50%) were included within bulk reports from charities reporting multiple incidents, whilst 616 (49.59%) were not.

Our regulatory response

We recognise the need for further analysis of our serious incident reporting data as a whole in order to allow us to share learning, good practice and areas for development.

The purpose of this would be to help charities ensure that they are responding appropriately to incidents which happen in their charities.

This might also include publishing regular analyses of the total number and nature of reports of serious incidents and their outcomes that charities can learn from and the public take assurance on.

“Deep dive” of historic records

The taskforce reviewed 5,501 records held by the Commission between 1 April 2014 and 20 February 2018 indicating a safeguarding issue in a charity.

The purpose of this work was to identify any gaps in full and frank disclosure by charities and to ensure charities and the Commission had taken appropriate follow-up actions associated with the incident reported.

The majority (4,808) of records related to serious incident reports, submitted by charities themselves. In addition, we reviewed 61 whistleblowing reports and 632 complaints or reports received from other regulators, agencies, or authorities (for example police, Department for Education, local authorities).

The 5,501 records related to 1,511 charities. It is notable that during this period (2014-18), there were around 167,000 charities on the register. Therefore, fewer than 1% (0.9%) of registered charities submitted a report of a serious safeguarding incident, and only 1.5% reported any kind of serious incident at all, whether around safeguarding, financial issues or anything else.

We accept that there may be a significant proportion of charities that do not experience safeguarding incidents, or only experience such incidents very rarely, due to the nature of their work. However, it seems unlikely that 99.1% of charities did not experience any reportable safeguarding issues over a 4 year period.

The work of the taskforce therefore indicates that, despite our work in recent months and years to encourage reporting by charities, we are seeing significant under-reporting.

44 charities were responsible for reporting approximately 55% of the total safeguarding incidents. We do not consider this necessarily as an indicator of concern; regular reporting is evidence of good practice in and of itself. Similarly, we recognise that serious incidents may occur more frequently within certain charities due to their size, or the nature of their activities, for example charities providing care or support to service users with complex needs or those with learning disabilities or mental health problems.

If a charity is likely to make regular multiple serious incident reports, our guidance signposts them on how to work with us to agree to submit bulk reports periodically, with particularly serious or significant incidents reported straight away.

Of the 5,501 records, just over 2,000 involved incidents the charities assessed as allegations of potential criminal behaviour. In all but one of these cases, we were told that these incidents were referred to the police. See further below.

Our regulatory response

We are concerned by low levels of serious incident reporting and must do more to address this. Whilst there has been an increase since the events of earlier this year, the vast majority of registered charities (99.1%) have not reported a serious safeguarding incident over the period reviewed.

We are further analysing the available data so that we can get a better picture of which charities are not reporting RSIs, take targeted action to improve the level of reporting where it is required and verify whether incidents have happened that have not been reported.

Findings

Our review did not identify any historical cases giving rise to serious and urgent concerns requiring us to take immediate remedial action, or where we had to engage with other law enforcement/safeguarding authorities about any ongoing risk or criminality.

The analysis identified only one case where it was unclear whether the charity had reported a potentially criminal matter to the police. Action was taken by us in that case and assurance was obtained that it had been reported to the police.

The review found that the Commission generally obtained sufficient assurance at the time the case was handled that all relevant risks associated with an incident were being managed.

In most cases, the charity was taking responsible and appropriate action to deal with the primary source of risk identified by the incident, and wider risks were also being managed, following a review of relevant policies and procedures.

However, it often took more than one round of correspondence to gain the information needed for the Commission to be assured. Often initial reports from charities were very brief summaries of the incident and did not provide the necessary detail.

The review also noted a lack of understanding in some charities of the threshold for reporting serious incidents. This resulted in over-reporting by some charities (reporting of incidents which do not meet the threshold of a serious incident). It also resulted in under-reporting by other charities (serious incidents not being recognised as such and reported), with incidents coming to our attention from other routes rather than the charity.

Example

A school failed an OFSTED inspection, and was required to submit an action plan to OFSTED within 3 months. The charity did not report this failed inspection result to us, as is expected by our RSI guidance. The Commission only became aware of the issue via a disclosure made by the Department of Education.

Example

A school bus was involved in a minor accident in which no child or adult was injured. This incident was reported to us by three different charities who used the bus service, despite there being no suggestion that the cause of the bus crash was non-accidental. An accident with no significant impact would be unlikely to meet the threshold for reporting.

The review noted that reports were not always made in a timely manner. This was particularly the case with reports of incidents of criminal activity, where trustees sometimes waited until police charges have been brought, or conviction secured, before reporting. This is at odds with our requirement to report promptly.

It also prevents us from being able check if the individual involved in the possible criminality is involved with other charities and/or to engage with law enforcement to see if they present risks elsewhere. Where criminal charges do proceed, it can be months or years before an outcome is reached.

If reporting is postponed until the end of that process, this can also mean a lost opportunity for the Commission to provide advice to the charity in the appropriate management of risk arising from that incident.

Our regulatory response

We have made swift clarifications to our existing guidance on reporting serious incidents to address one or two areas where charities have indicated it might not be clear enough and uncertainty identified from the review as well as ensuring its language is in line with the safeguarding strategy updated and published in November 2017.

In the medium term, we continue to review our guidance to ensure it is as clear and user-friendly as possible.

Looking ahead, we are also exploring the development of a new digital tool for reporting serious incidents. The purpose of this would be to make it easier for charities to provide the information we need at the outset.

In the meantime, we are developing a checklist to sit alongside the RSI guidance to help better inform trustees about what key information we need about different types of incident when reported. These checklists will be available in the next few weeks.

Bulk or multiple reports of serious incidents

The review found that many of the bulk /multiple reports did not contain sufficient and/or consistent detail to fully assure the Commission about the charity’s handling of all of the safeguarding incidents reported.

As part of our review, the reviewers therefore wrote to those charities to ask for more information. Specifically, we asked them to provide examples of how they dealt with certain types of safeguarding incidents that were a regular occurrence for their charity because we had identified that we needed further assurance about how each of the charities and their leadership were assessing and managing the risks as a whole from themed or repeat types of incident.

Having reviewed the responses from the selected charities, we were generally assured that the charities were handling individual incidents appropriately, for example reporting to the police where it was criminal. In other words, we are confident the challenge was with the consistent quality of reporting of incidents, not with the management of those incidents by the charities concerned.

A number of the reports did not provide enough detail to be able to assess whether all the expected action had been taken.

Example

In one case there was a description of an incident given simply as “death of a service user in hospital”, with no other information about how the death came about, why it was considered to be a serious incident, or how the actions taken by the charity in response demonstrate compliance with our published safeguarding guidance.

In the majority of cases where sufficient information was available, it was clear from the report that the charity was taking action to deal with the primary source of risk identified by the incident. However, there was rarely sufficient information to demonstrate that charities were considering, identifying and learning the wider lessons arising from an incident.

Example

A number of reports related to incidents where a member of staff was found to have abused a beneficiary of the charity. The reports usually demonstrated that the charities took prompt disciplinary action to dismiss those individuals.

However, it was often not clear from those reports that the charity had considered wider risks, and the outcome of any wider lessons reviews, for example whether the charity’s recruitment and vetting policies were sufficiently robust to mitigate the risk presented by employees with a known history of criminal behaviour.

Similarly, it was often not clear in the reports whether steps had been taken to deal with the ongoing risk posed by the perpetrators to others outside the charity. For example, it was not always clear whether the charity had made a referral to the Disclosure and Barring Service (‘DBS’) in relation to the dismissal/removal of employees for misconduct on safeguarding issues where they were in regulated positions.

Our regulatory response

We are conducting a rolling programme of engagement with charities that submit multiple serious incidents reports. This began with round table meetings over the summer with over 30 charities. This is leading to a consistent framework for multiple reporting, which is workable for the charities and both provides consistent key data to the same standard across all the charities and enables the assurance required by the Commission to be provided more easily and quickly.

Engagement of charities with other stakeholder agencies

Local authority

Of the cases reviewed, it was unusual to find a case where a significant safeguarding concern had arisen and the Local Authority Designated Officer (LADO) was not involved, following a referral by the charity. Positively, the few cases where a referral was not made tended to be because the Designated Safeguarding Lead (DSL) within the charity considered the incident did not reach the threshold for a referral, rather than there being a failure to consider referring.

Police

In the vast majority of cases where a criminal offence had potentially occurred, charities were promptly making reports to the police. In cases where there was doubt about whether to report a matter to the police, there was evidence that charities sought advice from the LADO, or other relevant stakeholders, and usually followed that advice.

The majority of charities had been able to provide a crime reference number and contact details, when prompted to do so by the Commission during the original engagement, for the purposes of verification of the crime report being made to the police/its details. However, not many charities provided this information proactively, when first reporting the incident to us, despite our guidance being clear that they needed to do so.

Whistleblowers

Whistleblowing reports, that is reports made by current employees, represented a very small proportion of the source of us being alerted to the events in a charity. Separate to the work of the task force, the Commission has been working to improve the experience of whistleblowers in raising concerns with us.

Our regulatory response

We have been conducting a detailed review of the way we respond to whistleblowers. The key aim of the review is to strengthen confidence among potential whistleblowers about making a protected disclosure to us, by ensuring that they can expect a consistent approach in the way we handle their concerns, and to receive appropriate feedback on progress.

We have published updated guidance on whistleblowing, that helps people better understand when, and how, they can report possible wrongdoing to us so that it is as easy as possible for people who make what is often a brave decision to come to the Commission with concerns.