Minimum excise tax

Updated 6 October 2014

1. Background: recent developments in the cigarette market

1.1 Introduction

A recent trend in the cigarette market has been the significant growth of the cheapest cigarette category. If this trend is indicative of a market shift towards cheaper cigarettes, it presents a risk to the effectiveness of tobacco policy in its role to protect future revenues and reduce smoking rates.

This consultation is a first step towards assessing whether a minimum excise tax (MET) could help reduce this risk.

This consultation explores the advantages and disadvantages of a MET, as well as potential impacts on the market for tobacco products. If, following full consideration of the responses, the government decides to proceed with a MET, further technical details of the MET model will be considered in due course.

Chapter 1 presents the case for how a MET may be a useful tool to support tobacco policy in its role to protect future revenues and public health. Chapter 2 explores the effectiveness of a MET and implications for the cigarette market. Chapter 3 seeks views on the impact on the hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) market. A summary of the consultation questions is supplied in chapter 4.

1.2 Tobacco tax revenues

Tobacco duty is an important contributor to the public finances, forming part of the government’s credible plan to reduce the UK’s debt. Revenues from tobacco duty were approximately £9.7 billion in 2013-14.

At Budget 2014, excise duty on all tobacco products was increased by 2% above RPI inflation. The government also announced that annual duty increases of 2% above inflation would continue until the end of the next Parliament.

These changes were announced so as to ensure that tobacco duties continue to contribute to the public finances. Reducing the affordability of tobacco products through taxation is also acknowledged to be very effective in encouraging smokers to quit and in discouraging young people from taking up smoking.

1.3 Recent developments in the cigarette market

Estimates of cigarette category market shares, as at 2009, suggest that consumers are switching away from more expensive cigarette categories, in favour of cheaper cigarette categories. This switch is often referred to as “down-trading.” As described in a recent study of the UK cigarette market, between 2001 and 2009 the market share of the cigarette categories at the higher end of the market broadly declined while the market shares of the lower end of the cigarette market broadly increased.[footnote 1] Graph 1.A is replicated from this study and illustrates these trends.[footnote 2]

Graph 1.A: Volume market share by price segment, 2001 to 2009

Chart illustrating volume market share by price segment from 2001 to 2009

Source: Gilmore et al. (2013) Figure 2: Volume market share by price segment, 2001 to 2009

As shown, the second cheapest cigarette category (Economy) continued to hold the largest market share in 2009 at approximately 50% of the market. However market share growth appears to have broadly plateaued between 2006 and 2009.

The market shares of the first and second most expensive cigarette categories (Premium and Mid-Price) both declined by approximately 10% each during 2006 and 2009.

In contrast, the market share of the cheapest cigarette category (Ultra-Low Price) doubled between 2006 and 2009, growing from approximately 10% to approximately 20%.

Changes in market shares can be due to a number of factors, including wider economic conditions, changes in smoking prevalence, exchange rate dynamics and price changes. However the trends described above are suggestive of a growing popularity of cheaper category cigarettes.

More recent estimates of the cheapest cigarette category market share in 2013 set it at approximately a third of the UK cigarette market.[footnote 3] This, combined with anecdotal evidence from industry suggesting that we are now seeing the emergence of a fifth, lower priced cigarette category, further lends support to the down-trading theory.

The market share dynamics described above have unsurprisingly coincided with a rising price gap between the most expensive and cheapest cigarette categories. The difference between real retail prices of the most expensive and cheapest cigarettes categories has widened by more than two thirds over the last 10 years.[footnote 4]

1.4 The risk posed by growth of the cheapest cigarette category

Tobacco duty revenues have been on a broadly upward trend in recent years. However, further continuation of the down-trading trend described above, along with a widening gap in the price differential between the cheapest and most expensive cigarette categories pose a risk to future tobacco tax revenue. This is due to the structure of tobacco excise duty.

Tobacco excise duty is made up of a specific (per stick) component and an ad valorem (percentage of the price) component. Because the ad valorem component is calculated as a proportion of the price, less revenue is received from cheaper cigarettes compared to more expensive cigarettes. A structural minimum tax level (such as a MET) may help mitigate this risk.

The market dynamics may also reduce the effectiveness of the tobacco duty regime to help protect public health. Growth at the lower end of the cigarette market allows smokers to switch more easily to cheaper category cigarettes, instead of reducing their smoking levels, in response to duty increases. Recent analysis shows that smokers respond more to price increases if they are unable to take advantage of lower prices offered by cheaper cigarettes.[footnote 5] In this way a structural minimum tax level may also help protect public health.

Question 1

Do you agree that the growing popularity of the cheapest cigarette category presents a risk to the future effectiveness of tobacco policy?

2. The case for a minimum excise tax (MET) for cigarettes

2.1 The MET as a tool to help support tobacco policy

A MET works by establishing a minimum tax level for a packet of cigarettes. The UK is currently one out of three EU member states which do not operate some form of a structural minimum tax level.[footnote 6]

A MET can either set a minimum level of excise duty (specific duty plus ad valorem duty) or a minimum level of total tax (specific duty, ad valorem duty plus VAT). The latter case is often referred to as a minimum consumption tax (MCT).

In the first case, the MET will establish a “trigger point” level of excise duty. For each packet of cigarettes on the market, the total excise duty is calculated in the usual manner by combining the specific (per stick) duty and the ad valorem (percentage of the price) duty. If this is above the “trigger point” level, it is left unchanged. If it falls below the “trigger point” level, the packet of cigarettes is automatically charged the “trigger point” level of excise duty. VAT is then applied at a rate of 20% of the retail selling price and added to the excise duty tax bill.

In the second case, the MCT will establish a “trigger point” level of total tax on a packet of cigarettes. For each packet of cigarettes on the market, the total excise duty is calculated in the usual manner by combining the specific (per stick) duty and the ad valorem (percentage of the price) duty, as before. Then the VAT is applied at a rate of 20% of the retail selling price and added to the excise duty. If this total tax level (excise duty plus VAT) is above the “trigger point” level, then it is left unchanged. If it falls below the “trigger point” level, then the packet of cigarettes is automatically charged the “trigger point” level of total tax. There is no need to add VAT at this stage, as it has already been included in the calculations as described.

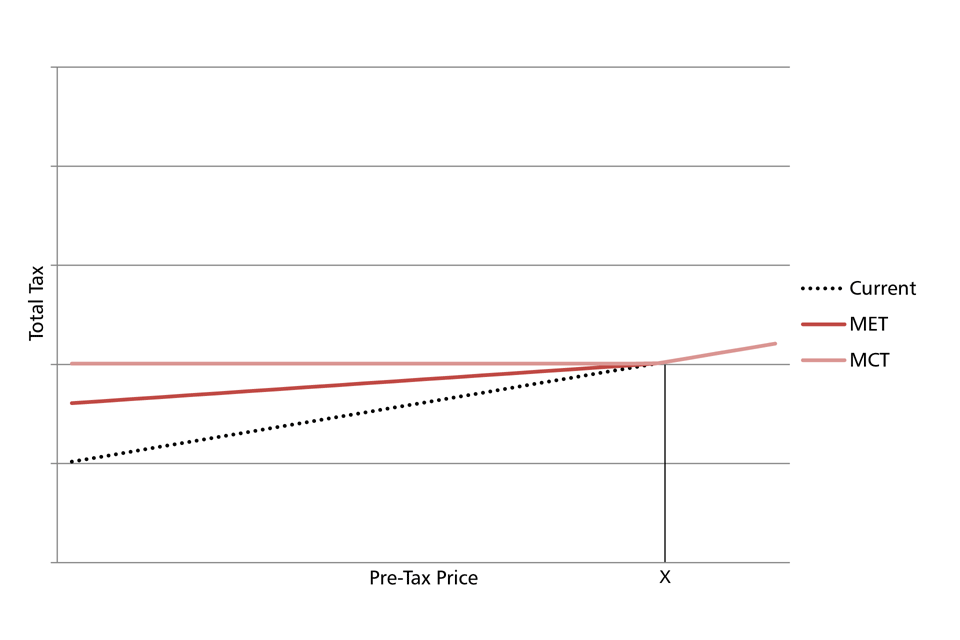

Graph 2.A below further illustrates these dynamics.

Graph 2.A: Impact of a MET and MCT on the total tax on a packet of cigarettes

Graph illustrating the impact of a minimum excise tax and minimum consumption tax on the total tax on a packet of cigarettes

The dotted “current” line shows the current total tax (duty plus VAT) on a packet of cigarettes, in the absence of any “trigger point” level of MET or MCT. It is upward sloping. Because the ad valorem and VAT tax liabilities increase as price increases, pre-tax prices and the total tax levels are positively related.

The point X denotes the pre-tax price level associated with the “trigger point” level of MET and the “trigger point” level of MCT.[footnote 7]

As the graph shows, above the “trigger point” level, (i.e. to the right of X) the total tax liability on a packet of cigarettes is left unchanged.

When a MET is established, as described above graph 2.A, any packet of cigarettes below the “trigger point” level of total excise duty (specific plus ad valorem duty) will be charged the MET level of duty. VAT will then be added to the total tax liability. This is why the MET total tax is flatter than the “current” line to the left of point X.

When a MCT is established, as described above graph 2.A, any packet of cigarettes below the “trigger point” level of total tax will be charged the MCT level of duty. This is why the MCT Total Tax line is a flat line to the left of point X.

These tax impacts have the potential to influence pricing outcomes in the cigarette market. This is why setting a structural minimum tax level such as a MET (or MCT) may be useful to help protect future revenues in the event of further down-trading. An illustrative example is presented in graph 2.B below.[footnote 8]

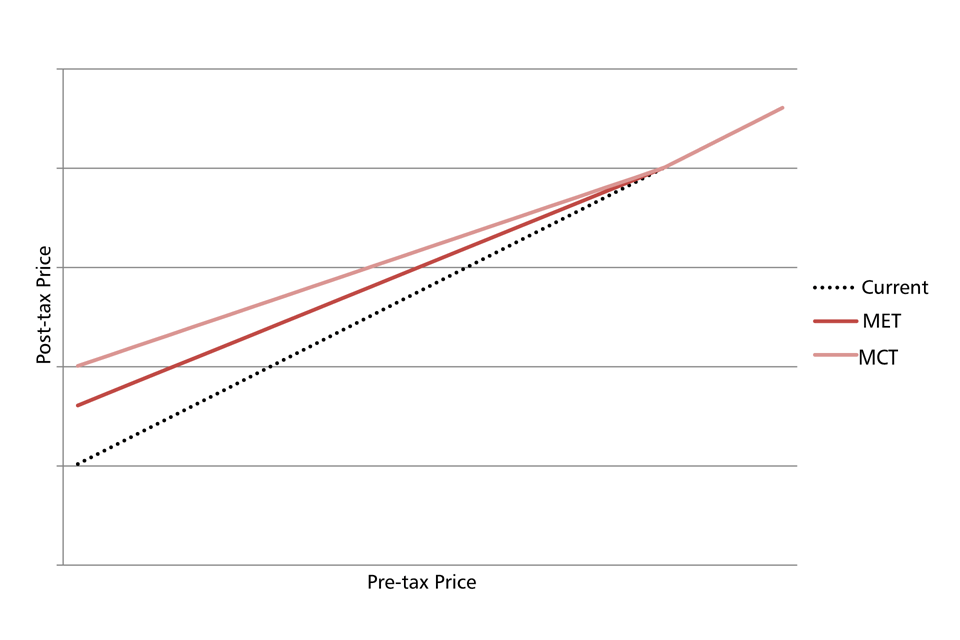

Graph 2.B: Impact of a MET and MCT on the price of a packet of cigarettes

Graph illustrating the impact of a minimum excise tax and minimum consumption tax on the total tax on a packet of cigarettes

Assuming that taxes are fully passed on to consumers, the higher tax liability arising from the introduction of a structural minimum tax level (compared to the “current” case) below the “trigger point” means that prices will rise at a faster rate than otherwise up to this point. This results in flatter price lines below this point. As a MET sets a binding level of excise tax (compared to a binding level of total tax), its price line is relatively steeper than the price line corresponding to the MCT case.

A MCT could have additional direct impacts on the hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) market. This shall be discussed further in chapter 3.

To summarise; as highlighted in graphs 2.A and 2.B above, while tobacco manufacturers and retailers would retain the power to set their own prices with a MET or MCT, establishing a minimum structural tax level has the potential to influence pricing behaviour and strengthen a price point below which cigarette prices are less likely to go. In this way, both options could limit the extent to which the lower end of the cigarette market can grow. This may be useful to help protect revenues against the backdrop of down-trading trends.

This could also help to ensure that the tobacco duty regime can continue to effectively protect public health, reducing the opportunity to down-trade in response to duty increases, rather than reducing smoking levels.

Competition in the cigarette market should be unaffected, because the policy under consideration is for a minimum tax rather than a minimum price. As highlighted in graph 2.B in particular, a producer with a lower-price business model can continue to sell their cigarettes at a lower price than others.

Question 2

Do you agree that a MET (or MCT) could provide a useful tool in helping to protect tobacco policy, by limiting growth at the lower end of the cigarette market?

2.2 The impacts of a MET on the cigarette market

The remaining sections of this chapter discuss issues which apply more broadly to any structural minimum tax level. For simplicity, the discussion shall focus on a MET until a MCT is revisited in chapter 3.

A MET is likely to have wider impacts on the cigarette market, which should also be considered. Two particularly important impacts are those on the illicit tobacco trade and the interaction between a MET and the pricing strategies of tobacco manufacturers and retailers.

When making any change to the tobacco duty regime, the possible impact on the illicit trade must be taken into account. As well as funding criminal activity, the illicit tobacco trade denies UK citizens tax revenue which could be spent on vital public services. The Exchequer loses nearly £150 million in duty and VAT for every 1% shift in consumption from duty-paid to illicit tobacco products.

Depending on the level at which it is set, a MET could raise prices at the lower end of the cigarette market, which may encourage consumers to enter the illicit tobacco market.

HMRC and Border Force have an established and effective strategy to tackle the illicit trade. This strategy has led to the long-term decline of this illegal trade. Since the launch of the first anti-fraud strategy in 2000, the illicit market for cigarettes has reduced from 22% to 9%. The government is also consulting on a range of measures to strengthen its response to tobacco smuggling.[footnote 9]

Question 3

What impacts would a structural minimum tax level, such as a MET, have on the illicit tobacco trade?

The second important impact of a MET on the cigarette market is its interaction with the pricing strategies of tobacco manufacturers and retailers. If a MET were to be taken forward, it would be set at such a level so as to influence tobacco manufacturers and retailers to set prices which, as far as possible, limit how low prices can go. Further details of what level that should be will follow as appropriate in due course.

However, the effectiveness of a MET risks being undermined if the tax is not passed on in full to consumers. This would depend on the extent to which tobacco manufacturers and retailers would be able to absorb a MET tax impact rather than pass it on to consumers in the form of price changes. We would welcome any further analysis and data to help further inform our understanding of this aspect of a MET.

Question 4

What design features should a structural minimum tax level, such as a MET, have so that it can effectively influence pricing behaviour in the tobacco market?

2.3 Alternative structural reforms to protect tobacco policy

There are alternative structural changes to tobacco duty which could be pursued instead of, or alongside, a MET. Rebalancing is one such option, whereby the specific (per stick) component of cigarette tax is increased, while the ad valorem (percentage of the price) component is decreased. This reduces the excise duty differential between the most expensive and cheapest cigarettes to reduce the cost advantage of cheaper cigarettes and discourage down-trading.

A MET is arguably a more precise tool to curb the growth of the cheapest cigarette category compared to further rebalancing. This is because while a MET only impacts at the lower end of the cigarette market, rebalancing changes impact on the entire cigarette market.

Rebalancing changes the total tax due on the most expensive cigarette category (by reducing the total tax due) and the cheapest cigarette category (by increasing the total tax due). Rebalancing also reduces the total tax differential between the mid-priced cigarette categories and the cheapest category. While arguably rebalancing reduces the incentive to move from the most expensive to the cheapest cigarette category, it is uncertain whether further structural changes would exacerbate the down-trading trend by encouraging movement from the mid-priced cigarette categories into the cheapest category.

Rebalancing changes were made at Budget 2011. Preliminary analysis suggests that following these changes, the market share of the most expensive cigarettes was slightly higher than previously forecast. Nevertheless, the growth in consumption of the cheapest cigarettes continued. However, this may have been as a result of changes in consumer behaviour or the wider economic environment.

The government keeps all taxes under review. Since 2011 the government has chosen to increase the specific component of cigarette excise duty above inflation each year, rather than make further rebalancing changes.

Question 5

Are there any other structural reforms to the tobacco duty regime that could help support tobacco policy if down-trading trends continue?

3. Impacts on the hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) market

3.1 The HRT market

Smokers may use HRT for a number of reasons. For some it is a unique product which is not directly substitutable with cigarettes. For others it is a cheaper alternative to cigarettes.

While HRT sales still contribute a relatively small portion to tobacco receipts (approximately a tenth of the market), the contribution of HRT to tobacco receipts has been growing. Over the last 10 years the percentage of tobacco receipts accruing from HRT has grown from 4% to 10%. The percentage of tobacco receipts accruing from cigarettes has declined from 94% to 88% during the same time period.[footnote 10]

3.2 The impact of a MET on the HRT market

Depending on the level at which it is set, a MET may increase prices at the lower end of the cigarette market. As well as potentially encouraging consumers to move into the illicit market, as discussed in chapter 2, this may also encourage consumers to move into the HRT market.

This presents an additional risk to the effectiveness of a MET to protect tobacco revenues, as less revenue is received from HRT compared to cigarettes.[footnote 11]

One possible mitigating option is to introduce an additional duty rise on HRT, above the increases announced at Budget 2014.[footnote 12] If passed through, this could reduce the price differential between the cheapest cigarettes and HRT, thereby reducing the incentive to down-trade.

Another option is to introduce a MCT, which would have a direct impact on the HRT market. As described in chapter 2, a MCT establishes a “trigger point” level of total tax (excise duty plus VAT), as opposed to a “trigger point” level of excise duty as with a MET.

The reason why a MCT affects the HRT market while a MET does not is because cigarettes and HRT are taxed differently. A MET only sets out a minimum level of excise duty for a packet of cigarettes. This will not apply to HRT because it is charged according to weight. However both cigarettes and HRT are charged VAT based on their selling price. Because a MCT establishes a minimum level of total tax (including VAT), the VAT component of the MCT minimum tax level would also apply to HRT. This would be likely to affect the lower (relatively cheaper) end of the HRT market, which in the absence of a MCT pays less VAT.

A MCT would therefore have an automatic impact on the HRT market, which, depending on the level at which it is set, could raise tax levels at the lower end of the HRT market.

Anecdotal evidence from industry suggests that consumers do not necessarily down-trade from one cigarette category to the next, but sometimes “jump” downwards through more than one category at a time. As described above a MCT could curb growth at the lower end of the HRT market. If this “jumping” behaviour also applies to shifts from the cigarette market to the HRT market, then a MCT could reduce the incentive to down-trade from cigarettes into HRT, thereby protecting tobacco policy.

While this consultation is interested primarily in a MET, we would also welcome any views on the relative merits of a MCT.

Both options risk encouraging current users of HRT to move into the illicit tobacco market. As described in section 2.2, HMRC and Border Force continue to effectively combat the illicit trade. This has helped to reduce the illicit market for HRT from 61% to 36% since 2000.

A further consideration relating to the HRT market is whether there is uneven growth among HRT categories. Unlike the cigarette market, a shift towards cheaper category HRT does not pose a risk to future tobacco excise revenues. This is because HRT excise duty, which is based solely on weight will remain the same regardless of the selling price.

Segmentation of the HRT market does however threaten the effectiveness of the tobacco duty regime to protect public health. This is because segmentation – if it is occurring – would allow consumers to switch to cheaper HRT brands instead of reducing their smoking levels, in response to duty increases. As discussed above, a MET would not have a direct tax impact on the HRT market. However a MCT would have a direct impact on tax, as a component of the MCT minimum tax level would also apply to the lower end of the HRT market. This could help curb uneven growth at the lower end of the HRT market and discourage down-trading within HRT.

We would welcome any analysis on the relative growth of the HRT categories to help inform our modelling of this aspect of the tobacco market.

Question 6

Do you think that additional duty measures or structural changes which impact the hand-rolling tobacco market would be required instead of, or alongside a MET?

3.3 Conclusion

Future tobacco duties may be at risk due to down-trading trends and the associated price differential between the top and lower end of the cigarette market. The continuation of these trends could mean that the market shares of cheaper cigarettes could continue to increase. Due to the structure of tobacco taxation, this would reduce the contribution of the tobacco duty regime to the public finances.

Establishing a structural minimum tax level such as a MET (or a MCT) is one option to reduce these risks and protect future tobacco revenues. It may also serve a public health goal, by helping to prevent further widening of the price gap between the cheapest and most expensive cigarettes, which is often associated with down-trading. We would welcome any views on the effectiveness of a structural minimum tax level such as a MET (or MCT), as well as views on the wider impacts on the tobacco market.

4. Summary of consultation questions

Question 1

Do you agree that the growing popularity of the cheapest cigarette category presents a risk to the future effectiveness of tobacco policy?

Question 2

Do you agree that a MET (or MCT) could provide a useful tool in helping to protect tobacco policy, by limiting growth at the lower end of the cigarette market?

Question 3

What impacts would a structural minimum tax level, such as a MET, have on the illicit tobacco trade?

Question 4

What design features should a structural minimum tax level, such as a MET, have so that it can effectively influence pricing behaviour in the tobacco market?

Question 5

Are there any other structural reforms to the tobacco duty regime that could help support tobacco policy if down-trading trends continue?

Question 6

Do you think that additional duty measures or structural changes which impact the hand-rolling tobacco market would be required instead of, or alongside a MET?

5. The consultation process

This consultation is being conducted in line with the tax consultation framework. There are 5 stages to tax policy development:

- Setting out objectives and identifying options

- Determining the best option and developing a framework for implementation including detailed policy design

- Drafting legislation to effect the proposed change

- Implementing and monitoring the change

- Reviewing and evaluating the change

This consultation is taking place during stage 1 of the process. The purpose of the consultation is to seek views on the policy design and any suitable possible alternatives. Consideration of the specific technical details of the MET (or MCT) model will follow in due course, should the decision be taken to proceed further with a structural minimum excise level.

5.1 How to respond

A summary of the questions in this consultation is included at chapter 4.

Responses should be sent by email to MET@hmtreasury.gsi.gov.uk or by post to:

MET consultation

VAT and Excise

HM Treasury

1 Horse Guards Road

London

SW1A 2HQ

All responses will be acknowledged, but it will not be possible to give substantive replies to individual representations.

When responding please say if you are a business, individual or representative body. In the case of representative bodies, please provide information on the number and nature of people you represent.

5.2 Confidentiality

Information provided in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be published or disclosed in accordance with the access to information regimes. These are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), the Data Protection Act 1988 (DPA) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

If you want the information that you provide to be treated as confidential, please be aware that, under the FOIA, there is a statutory code of practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals with, amongst other things, obligations of confidence. In view of this it would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on HM Treasury.

HM Treasury will process your personal data in accordance with the DPA and in the majority of circumstances this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to third parties.

5.3 Consultation principles

This consultation is being run in accordance with the government’s consultation principles.

If you have any comments or complaints about the consultation process, please contact:

Oliver Toop

Consultation Coordinator, Budget Team,

HM Revenue & Customs

100 Parliament Street

London

SW1A 2BQ

Email: hmrc-consultation.co-ordinator@hmrc.gsi.gov.uk

Please do not send responses to the consultation to this address.

-

This section is based on the analysis contained in: Gilmore, Anna B., et al. “Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: the example of the UK cigarette market.” Addiction 108.7 (2013): 1317-1326. ↩

-

Graph 1.A is a replication of Figure 2 in Gilmore et al. (2013) Copyright © 2013 Society for the Study of Addiction. It is based on data from the General Household Survey (GHS) (now known as the General Lifestyle Survey) and Nielson. G = GHS data. Ni = Nielson data. ULP = Ultra-Low Price. Others-G = market share held by brands that were not identified in the GHS list (this includes “brand not found,” i.e. the smoker names the brand, but it is not identified in the GHS list; “smokes two brands equally” or “no regular brand” – for the last two categories the survey does not attempt to record a brand) or that were identified in the GHS, but for which Gilmore et al. were unable to identify price data and thus to allocate to a price segment; the brands in this second group all had very low market shares. Further detail on the data series are available in Gilmore et al. (2013). ↩

-

Tobacco Industry Factsheet, Action on Smoking and Health, August 2014. ↩

-

Cigarette price data is available from the most recent HMRC Tobacco Factsheet and real exchange rate data is available from the Office of National Statistics. 1999 has been taken as the base year. The cigarette categories referenced are consistent with the definitions used by HMRC’s Tobacco Factsheet. ↩

-

Ross, Hana, et al. “Do cigarette prices motivate smokers to quit? New evidence from the ITC survey.” Addiction 106.3 (2011): 609-619. ↩

-

See The EU Excise Duty Tables: Part III – Manufactured Tobacco. ↩

-

Graph 2.A depicts the X level of pre-tax price to be the same for both the MET and MCT case. However, this does not necessarily have to hold. ↩

-

An implicit assumption of Graph 2.B is that there is a positive relationship between pre-tax prices and production costs. A higher cost producer must charge a higher pre-tax price than a lower cost producer, so as to recoup the higher production costs. ↩

-

The government will be consulting on legislative changes to address the growing threat of raw tobacco being used in the production of illicit tobacco products. The government will also consult on the implementation of the World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Illicit Trade Protocol later this year. ↩

-

Data on the contribution of HRT receipts to total tobacco receipts can be found in the most recent HMRC Tobacco Factsheet. ↩

-

HRT is currently subject to a duty of £180.46 per kilogram. Cigarettes are currently subject to a specific duty of £184.10 per 1,000 cigarettes and an ad valorem duty of 16.5% of the retail price. We do not make any assumptions about the amount of tobacco used in a hand rolled cigarette. ↩

-

Budget 2014 announced that HRT duty (as well as duty on all tobacco products) would increase by 2% above RPI inflation in 2014 and also each year until the end of the next Parliament. ↩