Summary of responses and government response

Updated 3 June 2020

1. Introduction and context

1) The purpose of the consultation was to obtain views on the management measures being considered by Defra and the Welsh Government for species of Union concern which are widely spread in England and Wales pursuant to Article 19 of Regulation (EU) No. 1143/2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species (‘the Principal Regulation). The consultation was launched on 18 July 2019, and ran for 8 weeks.

2) The Principal Regulation requires effective management measures to be put in place for widely spread species, so that their impact on biodiversity, the related ecosystem services and, where applicable, human health or the economy are minimised. Management measures must be aimed at one or more of the following three purposes: eradication, population control or containment.

3) The consultation set out proposals for management measures for 14 species of Union concern that have been identified as being widely spread in England and Wales. It sought views on management measure aims, general management measures (those relating to activities which are not restricted by the Principal Regulation and therefore do not require a licence under the Invasive Alien Species (Enforcement and Permitting) Order 2019 (‘the Enforcement Order’)) and licensable management measures (those relating to activities which would be unlawful if undertaken without being authorised by a licence granted under article 36(2)(b) or 36(2)(c) of the Enforcement Order).

4) Defra and the Welsh Government normally aim to publish a summary of consultation responses within 12 weeks of the close of a consultation. In this case, the summary of consultation responses was due to be published before 12 December. However in the light of the general election and the associated pre-election period, it was not possible to publish the full summary document and government response until after the new UK government had been formed.

5) Prior to the publication of this summary of responses and government response, Defra and the Welsh Government issued an interim response (on 1 November 2019) setting out our joint position ahead of the Enforcement Order coming into force on 1 December. The interim response was updated on 20 December 2019.

1.1 EU Withdrawal Agreement and the Enforcement Order

6) The EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 ensures that existing EU environmental law continues to have effect in UK law following the UK’s departure from the EU.

7) The Invasive Alien Species (Enforcement and Permitting) Order 2019 which puts in place licensing provisions relating to management measures and sets out the penalties for breach of the restrictions in the Principal Regulation, defences and other enforcement-related provisions, came in to force on 1 December 2019.

2. Respondents

8) A total of 722 responses were received during the consultation period. The majority of responses were submitted via the CitizenSpace online portal, with a small number being submitted via emails and as hardcopy responses.

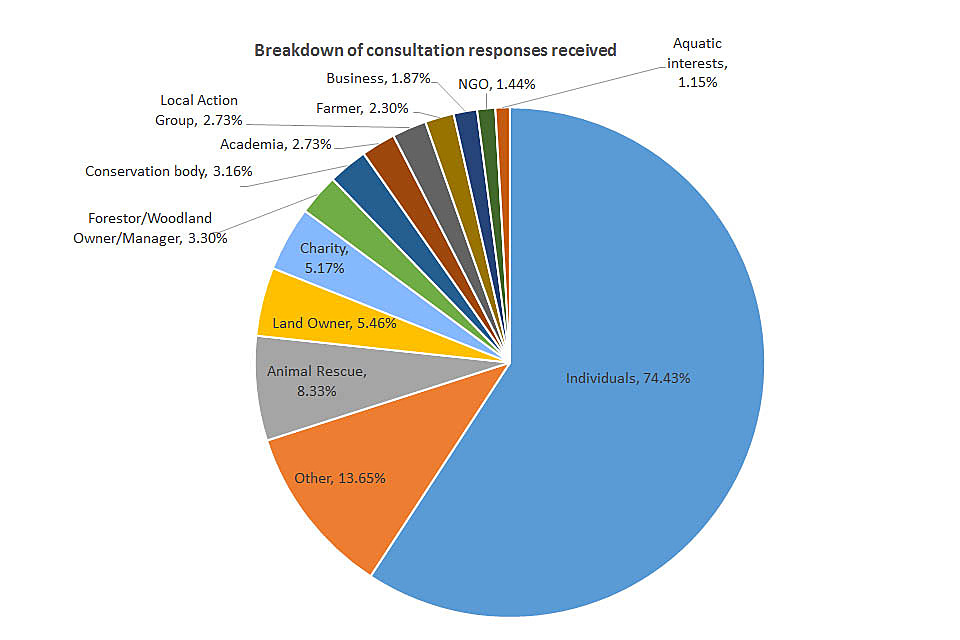

9) Responses were received from a wide range of respondents including private individuals, conservation groups, charities and trade associations (See Figure 1 for the breakdown of responses by sector/interest). A number of respondents made points that, although acknowledged, are outside the scope of this consultation. These included comments that related to the control of species which were not included in the list of 14 species under consideration, such as Japanese knotweed and non-native deer species other than muntjac.

10) Over three quarters of respondents submitted responses that appeared to be in response to, or along the same lines as, information supplied as part of letter writing campaigns. The majority of these respondents were opposed to measures which referenced lethal control including culls and/or eradication. Of those respondents who did not appear to be responding as part of, or in a similar vein to, the letter writing campaigns, the majority of respondents indicated that they were generally supportive of the proposals.

11) A list of the organisations which responded to the consultation is provided at Annex A.

Figure 1 – breakdown of consultation responses received

Pie chart showing a breakdown of respondents by type

| Type of respondent | % of responses received |

|---|---|

| Individuals | 74.43% |

| Other | 13.65% |

| Animal Rescue | 8.33% |

| Land Owner | 5.46% |

| Charity | 5.17% |

| Forestor/Woodland Owner/Manager | 3.30% |

| Conservation body | 3.16% |

| Academia | 2.73% |

| Local Action Group | 2.73% |

| Farmer | 2.30% |

| Business | 1.87% |

| NGO | 1.44% |

| Aquatic interests | 1.15% |

3. Summary of responses to questions and government response

12) Questions 1 – 5 of the consultation document are listed below.

Q1. Would you like your response to be confidential?

Q2. What is your name?

Q3. What is your email address?

Q4. Who do you represent?

Q5. What geographic region do your responses relate to?

13) Questions 6 - 12 of the consultation document were questions about the proposed aims for management measures, general management measures and licensable management measures.

14) Summaries of responses to each of Q6 - 12, along with the corresponding government responses are provided below.

15) Summaries of responses and government responses relating to the letter writing campaigns and to Appendix D of the consultation document (proposals relating to Signal crayfish) are provided separately.

4. Question 6: What are your views on the proposed aims for the management measures set out in Appendix A?

4.1 Summary of responses to Question 6

16) Respondents who provided more detailed comments on the aims in general, most commonly suggested that the aims needed to be more specific and quantifiable (including targets, rationale for control, timescales, resourcing and extent) and that they needed to be realistic to allow management effort to be prioritised, coordinated, cost-effective and achievable so the benefits are sustainable.

17) Some respondents highlighted the importance of good communication when planning, developing and undertaking control measures. It was suggested that this is particularly relevant when control measures for animals are being implemented. A mixture of respondents, particularly those representing aquatic interests, referred to the importance of the promotion of good biosecurity and said that the ‘Check, Clean, Dry’ biosecurity campaign should be more prominent.

18) Conservation and landowner groups emphasised the importance of local knowledge of both the landowner and land manager, the importance of mapping and reporting populations and recommended that support for Local Action Groups should be developed to maximise effective management. The importance of restoring native species where action has occurred to control invasive alien species was also put forward along with support for public money being spent both on research into effective management and to support those undertaking control action given the public benefits that are derived from management.

19) A cross-section of respondents suggested the enforcement framework needed to be strengthened.

Plants

20) Several respondents commented on the aim for widely spread plant species being too limited in its reference to Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), recommending expanding the aim to include areas upstream of important ecological sites and referring to rare and scarce native flora.

21) Other respondents felt that there was too much focus on ecologically sensitive sites, and that this took no consideration of the feasibility of management measures. Others felt that targeting either newly established populations and/or well established ‘primary sources’ with high risk spread (such as in riverine habitats and near railways and roadsides) would have wider and greater impact in terms of reducing spread to new areas and controlling sources of infestation. Some commented that focus on ecological sites should not cause an additional financial or administrative burden on landowners and that funding should be allocated to allow for optional management of riverine species in order to reduce the flood risk potential, particularly due to the increased risk due to climate change.

Animals

22) Some of those who agreed that wild animals need to be managed for a variety of reasons, including by lethal control methods, highlighted the need for transparency around decision making. They felt that a process was needed whereby the decision to undertake management, and the reasons for the choices made, are clear and based on robust scientific evidence demonstrating that the programme would result in long-term benefits. Respondents also suggested that clear objectives should be set, with a well-defined endpoint agreed by all stakeholders at the beginning of the project, so that all understand what success, or failure, looks like.

23) Several respondents recommended that the wording for the animal species related aims be extended to include references to feasibility, “to eradicate in the wild where possible using humane measures, and where outcomes are achievable and benefits are sustainable”. Others also suggested further expanding the aims to explain why action was necessary. For example, ‘….eradicate in the wild where possible… therefore reducing its impact on native biodiversity and ecosystem services, and wider socio-economic impacts.”

24) Whilst accepting that eradication is desirable for certain species, some respondents raised concerns around the feasibility of eradication or control of spread, particularly for very widely spread species including muntjac and grey squirrel. Some respondents advocated a coordinated, national response to manage these species. Some expressed disappointment at the proposed closure of the Deer Initiative; asking Defra and the Welsh Government to ensure the continuation of a strategic management plan for deer. It was further suggested that more research, evaluation and monitoring is required as a starting point to better understand these widely spread listed species in the UK. A point was made that there is a potential conflict between the practicalities of achieving control of muntjac using shooting and additional restrictions on firearms currently under consideration.

25) For grey squirrel, a broad range of respondents emphasised the need for the aim and resources to focus on the prevention of establishment in areas where red squirrels are currently able to thrive. They also highlighted the importance of funding for long-term control and consideration of how invasive alien species management is integrated within other land management policies, namely Countryside Stewardship and Environmental Stewardship in England and GlasTir in Wales.

26) For terrapins, respondents generally indicated that the focus should be on reducing further introductions of turtles into the environment rather than controlling existing populations in the wild. Others recommended an additional aim regarding regulation of trade, including an evaluation of the current standards for trading, suggesting improved business and public awareness would be an important element in reducing private collections.

4.2 Government response to Question 6

27) A number of respondents suggested that the aims needed to be more specific and realistic to allow management effort to be prioritised, coordinated, cost-effective and achievable so the benefits are sustainable.

28) The aims set out in the consultation document were provided as proposed over-arching statements of intent, setting out the overall desired direction of travel. We consider that specific statements defining targets and outcomes etc. would form part of developing proposals for taking action in line with species-specific management plans such as the Action plan for wild deer management in Wales or as part of proposals for taking site-specific action that might form part of licensable management action.

29) We consider lethal control to be necessary approach in some circumstances to protect the environment. However, where practicable, non-lethal measures may be explored for some animal species. Eradication will continue to be included in the aims for widely spread species (Annex B). The government will continue to support research, such as methods of biocontrol, to support this aim.

30) Responses regarding suggestions for re-phrasing the wording of the aims have been considered and the revised aims are attached in Annex B of this document.

5. Question 7: What are your views on the general management measures set out in Appendix B?

5.1 Summary of responses to Question 7

31) Respondents who provided more detailed comments on the general management measures most commonly referred to the importance of research into methods of detection, control and eradication, the need for government-led or better-coordinated management approaches, better monitoring and maintenance work following control and the additional resources needed to fund this work.

32) There was general support for increased awareness-raising about these species, their ecological and socio-economic impacts and the relevant legal restrictions, legal obligations, control methods and available funding streams. A number of respondents commented on the issue of internet sales and questioned how this could be adequately regulated.

Plants

33) Respondents were generally supportive of the general measures listed for widely spread plant species. Several respondents supported the ‘Be Plant Wise’ campaign but recommended that it be updated to include all relevant widely spread species of Union concern. Better communications and awareness-raising was also a common theme with suggestions for better labelling of plants to include their impacts, confirming landowner responsibilities and providing links to further information so that buyers can make more informed decisions. Some respondents also highlighted issues surrounding the possible future loss of certain pesticide products from the market, which have been used to control IAS plant species.

34) In general, respondents were supportive of the use of, and further research into, biocontrol measures for plants, quoting initial success with trials on Himalayan balsam.

Animals

35) Of those respondents who recognised that the use of lethal control methods may be necessary in certain circumstances, some sought reassurance that such action is monitored to ensure compliance and is conducted humanely. Whilst successful eradication programmes were referenced such as black rats on Lundy and grey squirrel on Anglesey, some felt a focus on eradication was not feasible or sustainable, and wished to see greater focus on implementation of non-lethal measures. It was also noted by respondents that the resources and effort involved in the coordination of eradication programmes are vast and any necessary eradication work must include plans with timescales, showing feasibility and sustainability.

36) Of those respondents commenting on the proposal to reduce the number of IAS in captivity over time, some suggested a stronger onus be placed on landowners and private collections so as to reduce populations and ensure that adequate measures are in place to prevent any accidental release. It was also highlighted that some of these species are not well adapted to captivity - particularly not in a domestic environment. Some respondents pointed out that this measure should be linked to the prevention of breeding in captivity. Others proposed a requirement for animals retained in captivity to be sterilised to avoid accidental breeding.

37) Some respondents were supportive of biocontrol methods for animals as an alternative to lethal control methods whilst others were dismissive of biocontrol for animals, particularly fertility control, indicating unwanted effects on other mammal species and issues with being able to effectively deliver such control across large regions of England and Wales.

6. Question 8: Are there any additional actions you think should be used as general management measures for particular widely spread species?

6.1 Summary of responses to Question 8

38) A number of respondents stated the current proposed actions were sufficient and that they had no further suggestions to add. Of those respondents supporting the proposed actions, a large proportion especially supported the need for awareness-raising across sectors, including updating the ‘Be Plant Wise’ campaign. A few respondents also suggested an awareness campaign could include how climate change is affecting the distribution of widely spread Invasive Alien Species.

39) Other general management measures suggested included the need for more research and for information and expertise to be accessed and shared more widely. Some also suggested the need for detailed and resourced action plans for each plant and animal species under consideration.

40) A measure suggested by a number of respondents was the use of financial incentive schemes particularly targeted at land mangers through stewardship schemes such as the Environmental Land Management system (ELMs) in England and GlasTir in Wales. The need for monitoring species was also highlighted by many respondents with one response suggesting a voluntary reporting scheme and the much greater use of data gathering and reporting via Local Environment Record Centres (LERCs).

41) Some respondents stated that organisations such as Forestry England should allow people to access their land for the purpose of trapping and shooting grey squirrels. Other suggestions for grey squirrel included ensuring sources of food such as garden bird feeders are squirrel proof, the reintroduction of predators such as pine marten, and restoration of broadleaf woodlands.

42) Further suggestions for additional actions to control muntjac were: working with relevant stakeholders, including Highways England, to continue their research and ongoing monitoring of muntjac deer and other deer species; exploring measures which minimise or mitigate the impact of this species, including woodland management and planning, highway design and roadside planting; and encouraging and supporting regional and local studies into the impacts of this species.

7. Question 9: Are there any actions you think should not be used as part of a general management measure for particular widely spread species?

7.1 Summary of responses to Question 9

43) Actions that some respondents stated should not be allowed as part of general management measures included allowing the keeping of specimens in private collections and the breeding of Invasive Alien Species. One respondent also suggested that the rust fungus control of Himalayan balsam should not be allowed, as they held concerns over the potential threat to indigenous species, and farm and horticultural seeds and crops, and others objected more generally to the use of herbicides and poisons as a means of controlling a species.

44) On the other hand, some respondents advocated retaining all possible approaches to invasive weed management including chemical, mechanical and biological, as long as they are justified on a risk assessment basis and are beneficial environmentally as well as financially.

45) It was suggested that the lethal control of animals as a general management measure was not always necessary, with additional respondents highlighting the need for alternative control methods.

8. Government response relating to general management measure – Questions 7, 8 and 9

46) There was a tendency for respondents to provide comments on a number of key themes in response to questions 7 – 9 rather than commenting on individual measures. As set out in our interim response issued on 1 November 2019, Defra and the Welsh Government will continue to support the general management actions being taken to manage widely spread species in England and Wales as set out in Appendix B of the consultation document. We will further consider how we can address key themes which emerged from the responses to question 7- 9: better communication, more strategic and coordinated action, increased resourcing and further research.

47) Defra and the Welsh Government agree that generating greater levels of public awareness and support is key to tackling invasive species and that this needs extra resourcing. Respondents frequently referenced the GB-wide campaign ‘Check, Clean and Dry’ which aims to reduce the risk of spreading aquatic invasive species. This campaign was refreshed in 2018. Respondents also referenced the ‘Be Plant Wise’ campaign, which aims to raise awareness among gardeners, pond owners and retailers of the damage caused by invasive aquatic plants and to encourage the public to dispose of these plants correctly. Respondents supported these types of campaign and suggested that the Be Plant Wise campaign be extended to include more examples of plant species of Union concern. Work is already underway to relaunch this campaign in 2020 and, as part of this, the inclusion of further species will be considered. We will continue to support the GB Non-native Species Secretariat’s annual ‘Invasive Species Week’ campaign and undertake to identify and take forward other priority awareness-raising work.

48) A well-established framework already exists, guided by the GB Non-native Strategy, for national, regional and local action to help reduce the detrimental impact of INNS. Defra, Welsh Government and their partners also work collaboratively to determine priority actions to manage IAS in England and Wales. However, we accept that this works needs to be extended and supported further to provide additional coordination and wider buy-in.

49) We will seek to support collaborative, landscape scale projects such as the ‘RAPID LIFE’ programme which is aiming to deliver a package of measures to reduce the impact and spread of IAS in freshwater aquatic, riparian and coastal environments across England and the ‘Wales Resilient Ecological Network (WaREN)’ which is aiming to formulate a framework for collaboration which will promote biodiversity and improve ecosystem resilience through developing a pan-Wales approach for the effective sustainable management of INNS in a strategic, prioritised and joined up way. We recognise the hard work and dedication of local volunteers who are a key resource in helping to manage many species and raise awareness.

50) The Defra and Welsh Government approach to combatting invasive alien species aligns with the internationally agreed hierarchical approach of: preventing species of Union concern from entering the UK, either intentionally or unintentionally; detecting the presence of species of Union concern as early as possible; and taking action to reduce the risk of further spread of widely spread species. By following this hierarchy we aim to take a risk-based approach to controlling widely spread species, taking into account the costs and benefits of action.

51) We will continue to encourage and support research into the impacts and control of these species including trialling new and on-going methods of biological control such as the rust fungus trials on Himalayan balsam and non-lethal means of control such as those being trialled by the UK Squirrel Accord.

9. Question 10 - What are your views on the proposed licensable management measures set out in Appendices C and D?

9.1 Summary of responses to question 10

52) There was a general acceptance from respondents (other than those responses connected to the letter writing campaign - see lines 76 - 82) that management measures are needed, but there was no clear overall agreement amongst respondents of what those measures should be. Some respondents felt that licensable management measures would lead to too much unhelpful bureaucracy and a resultant reduction in control action being taken. Many raised concerns about animal welfare and called for appropriate guidance to be issued and enforced. Some respondents raised concerns regarding transport of both animal and plant species and the consequential risks of accidental release to areas previously uninhabited by those species.

Plants

53) The majority of respondents who commented on the proposed licensable management measures for plants were supportive of the examples provided. Some respondents felt that a key omission was the use of plant material, live and dead, for training and educational purposes. There was a suggestion from the Property Care Association that they could assist by developing a code of practice for the use of invasive alien plant material in training and education. In line with the comments under Q6, several respondents commented that focus on ecological sites should not cause an additional financial or administrative burden on landowners.

Animals

54) The majority of respondents who supported the proposals for licensable management measures for animals appeared to accept that measures aimed at population control, containment or eradication are needed. However, some also felt that lethal control/euthanasia should only be used as a last resort and that the government should be transparent about the fact that management measures may lead to an increase in euthanasia of grey squirrel and muntjac deer, because they are not suited to being kept in captivity. It was also stated that facilities that will be required to undertake euthanasia must be given the necessary guidance to do so humanely.

55) In line with the comments in previous questions, many respondents felt that the keeping of animals in captivity for the remainder of their natural lives was inappropriate. However, the reasons for this response differed between those who felt this approach was not in the interest of the animals for animal welfare reasons and those who felt the keeping of these animals in captivity undermines the public message that these species are highly invasive. Some respondents suggested that animals should not be held in captivity but should, as a minimum, be returned to the wild after contraception is administered.

56) In the case of terrapins, it was suggested that due to their low numbers in the wild and apparent lack of breeding success in UK temperatures it would be both appropriate and feasible to remove small, isolated populations from the wild and subsequently keep them in a licensed, regulated facility. For muntjac and grey squirrel, it was suggested that due to their high numbers and high success in breeding it would not be realistic or humane to keep large numbers of these species in captivity.

57) A number of respondents commented on the difficulty of controlling grey squirrel and muntjac. Reasons advanced mainly included their widespread nature, the lack of coordinated control work between land areas and the lack of success in current efforts to significantly reduce numbers, with one or two notable exceptions (e.g. grey squirrels on Anglesey). Many respondents advocated the use of widespread contraceptive programmes as a means of control. However, whilst understanding the appeal of fertility control on ethical grounds over lethal control, others highlighted significant concerns over the selectivity of currently available contraceptive measures and the potential for unintended impacts on other wild mammal species and the feasibility of being able to deliver fertility control to a sufficient proportion of the target population.

58) One respondent suggested the measures described for signal crayfish could, in part, be relevant for Chinese mitten crab, although they did not propose the encouragement of capture and commercial use of Chinese mitten crabs stating this could potentially lead to an established UK fishery and an associated risk that the species could be spread via illegal (unlicensed) activity.

10. Question 11: Are there any additional actions you think should be allowed as a licensable management measure for a particular widely spread species?

10.1 Summary of responses to question 11

59) A number of respondents suggested adding additional requirements to the management measures proposed in Appendix C rather than new, additional measures. Some respondents stated that surveying and monitoring should form part of the conditions of licences involving trapping, lethal control, keeping or transport of live specimens in order to help understand the range and spread of these species. A recommendation was made that it should be a condition of any licence that data on the location and management undertaken be shared with Local Environment Record Centres (LERCs). Another respondent recommended that those operating under a licence involving lethal control should record quantities dispatched and submit the data to Natural England or Natural Resources Wales.

Plants

60) It was stated that Appendix C did not specifically address the use of plant material, live and dead, for training and educational purposes. Such use would clearly need to avoid associated risks, e.g. ensuring that preserved seeds were no longer viable and appropriate disposal post training. It was suggested that Defra approach the Property Care Association to develop a code of practice for the use of invasive plant material in training and education.

61) Some respondents from the farming and property sector thought a derogation or mechanism to use herbicides restricted by the Health and Safety Executive would be beneficial on widely spread plant species, to be used on a case-by case basis, in instances where no better control methods are available or feasible or where the benefit outweighs the risk.

Animals

62) Respondents were mostly supportive of fertility control being used as an additional management measure for widely spread animal species. Methods suggested were surgical sterilisation and contraception. Some respondents felt that fertility control should be used instead of lethal measures.

63) Several respondents thought that subsidies and/or incentives should be used to encourage the management of widely spread animal species. Suggestions included: incentivising the harvesting of meat for consumption; government-funded traps; and no close season for hunting and night shooting. Additionally, some respondents commented that only trained individuals and professionals should undertake lethal control, to ensure it is carried out humanely and safely.

64) Some respondents, particularly animal welfare charities, thought there should be conditions included in the management measure licences to ensure compliance with the Animal Welfare Act 2006.

11. Question 12: Are there any actions that you think should not be allowed to be used as part of a licensable management measure for a particular widely spread species?

11.1 Summary of responses to question 12

65) Other than those respondents who did not support lethal control in any circumstances, very few respondents put forward suggestions relating to actions they thought should be excluded from licensable management measures.

66) As set out above, there was a strong response against management measures involving lethal control, including culls and/or eradication, particularly from individuals. Some respondents were opposed to the use of specific lethal controls such as snare traps, and low calibre firearms. Many individuals highlighted animal welfare as being the motivation for their concerns and one charity highlighted that management methods used on muntjac deer must adhere to the restrictions contained in the Deer Act 1991.

67) Some respondents, including local authorities and charities, expressed concerns about the use of biological controls, particularly if they are genetically modified, e.g. gene drive technology. This can involve a number of genetically modified individuals being released into the environment either to control or eradicate a target population. It was suggested that evidence of its safety in the natural environment is limited and a precautionary approach should be taken.

68) A number of respondents said they were against the use of pesticides for control of animals or plants. Respondents cited impacts on non-target species, damage to the environment and human health as concerns.

69) Some respondents stated that widely spread species should not be kept in captivity under any circumstances. Additionally, some respondents said that they did not think widely spread species should be released as part of a management measure. In contrast, some respondents stated widely spread species should only be kept and released for scientific research purposes.

12. Government response relating to licensable management measure – Questions 10, 11 and 12

70) As set out in our interim response issued on 1 November 2019, Defra and the Welsh Government will implement licensable management in line with the proposals set out in Appendix C of the consultation, subject to the exceptions in paragraphs below. Management measures for Signal crayfish are dealt with separately.

71) Management measure licences may additionally be considered to allow widely spread invasive plants to be transported, and kept (in a biosecure manner), for the purposes of public education to help the identification of these species in the wild to aid in their eradication, population control or containment. We will liaise with the Property Care Association regarding their offer to develop a code of practice for the use of invasive alien plant material in training and education.

72) Specified kinds of facility will be able to apply for a licence in some circumstances to keep widely spread animal species taken in from the wild. Such licences will be considered on a case-by-case basis. In the light of welfare concerns raised in the consultation, Natural England and Natural Resources Wales have been considering appropriate conditions for licences allowing keeping. Natural Resources Wales and Natural England’s licence application form for keeping will require a vet’s statement verifying that animals are securely contained, their welfare needs are met, and that they are unable to breed. This is to ensure that any animals kept in this way are cared for properly and their welfare needs are met. Additionally, animals kept under licence will be required to be microchipped, so that there is a record of animals being kept across England and Wales.

73) For grey squirrels, such licences will not be available for facilities located in or near areas where red squirrels are present, or in locations where grey squirrels are absent.

74) It is not possible to license the release of IAS species for the purposes of rehabilitation. The release of IAS species, post rehabilitation, is not a matter falling within the scope of the consultation, as this activity cannot be seen to be directed at a management measure aim i.e. eradication, population control or containment. It was suggested that sterilised animals could be released as part of control methods. Sterilisation, however does not prevent live animals behaving in a way that could be damaging to the environment, or reduce their impact on native biodiversity throughout the course of their lives. We therefore do not see sterilisation as an effective way of managing the impact of these animals in the environment.

75) A number of respondents commented on the difficulty of long-term, sustainable control of grey squirrel and muntjac. Defra and the Welsh Government recognise that efforts to date have not resulted in a significant reduction in the numbers of muntjac. The Deer Initiative is due to cease its operations in March 2020. In Wales, some of the work of the Deer Initiative Wales will be taken forward by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust. Natural Resources Wales are considering how other measures in the Action plan for wild deer management in Wales can be progressed. As stated in paragraph 29, we confirm that although eradication is included as a licensable management measure, for widely spread species that are very common it may only be feasible in limited circumstances. We do consider lethal control to be necessary approach in some circumstances to protect the environment. However, where practicable, non-lethal measures should be explored for some animal species.

13. Letter writing campaign

76) There was a letter campaign response to the consultation, and responses followed a similar template. There were also a number of additional individual responses which expressed the same viewpoint as the letter writing campaign both in theme and tone. These responses made up a significant proportion of the total responses to the consultation, however many were single line responses for each question which did not present any evidence to support their statements.

77) All responses have been analysed and considered; however, the statements that were threatening in tone or significantly off topic, are not addressed in the government response below.

78) A significant proportion of these responses called for an exemption to the prohibition of re-release into the wild following rehabilitation of an injured animal, particularly for grey squirrels, and a smaller number for muntjac and Egyptian goose.

79) A number of key themes were identified within these responses these were:

i. The proposals in the consultation will have a negative impact on the welfare of grey squirrels, muntjac and Egyptian geese;

ii. Rescue centres will suffer a financial and/or ethical impact if they cannot release these three species;

iii. The EU legislation has been misinterpreted by the UK;

iv. Lethal measures to control invasive species should not be used under any circumstances, and that the killing of these species is morally and ethically wrong;

v. These species should not be seen as invasive, and that this is discriminatory towards animal species based on impact and origin;

vi. Keeping in captivity would be detrimental to the animal’s welfare and wellbeing.

80) In addition, the majority of responses which highlighted points regarding grey squirrels made additional further points as summarised below:

i. The evidence used to list grey squirrels as a species of Union concern was invalid or biased;

ii. Grey squirrels have not impacted red squirrel populations, and that population decline in red squirrel is due to historic human persecution and habitat fragmentation. Additionally that grey squirrels may not have played a role in spreading squirrel pox to red squirrel populations;

iii. Current red squirrel populations are actually Scandinavian, and therefore not native. Also that red squirrel are not endangered globally. We assume that these points seek to imply that the UK population should not be protected to the extent it is currently;

iv. Grey squirrels that have been taken into captivity could be returned to the wild after being given contraception;

v. Oral contraception should be used instead of lethal control measures. This was proposed even in areas where red squirrels are present. Responses stated that it would be possible to replace red squirrel populations with reintroductions from the continent.

vi. The numbers of rescued grey squirrels is statistically insignificant – and that release will have no impact on a wider scale;

vii. Having to euthanise injured rescued squirrels would be distressing to the public, wildlife aid staff and vets.

81) The key additional point relating to muntjac is summarised below:

i. The risk assessment for this species questions the feasibility of eradication in the UK.

82) The key additional point relating to Egyptian geese is summarised below:

i. The slow expansion of Egyptian geese in the UK and relatively low numbers should make them exempt from any lethal control measures.

14. Government response relating to letter writing campaigns

83) As set out in the consultation document, the Principal Regulation imposes strict restrictions on species known as ‘species of Union concern’. Whilst the UK is no longer an EU Member State, during the transition period the government is under a legal obligation to comply with EU law and all prohibitions and obligations under the Principal Regulation continue to apply.

84) We are, therefore, of the view that there is no provision under the Principal Regulation which would enable government to allow the species under consideration in the consultation to be taken in from the wild, rehabilitated and released back in to the wild. This does not meet the requirement for management measures to be aimed at eradication, population control or containment.

85) As set out above, respondents suggested that for grey squirrel and muntjac, keeping in captivity until the end of an animal’s natural life, would be detrimental to their welfare and wellbeing, and some suggested that release could take place following sterilisation. We acknowledge this point; sterilised animals, however, once released, would continue to have negative impacts on the environment, and native biodiversity throughout the course of their lives. We are therefore unable to recognise the release of these individuals back into the environment as a valid licensable management measure.

86) To address respondents’ concerns as far as possible regarding keeping in captivity, Natural England and Natural Resources Wales will require any premises applying for a licence to keep and move these animals to pass a veterinary inspection and to be able to demonstrate that they can care for the animals and meet their welfare needs.

87) We consider lethal control to be a necessary approach in some circumstances to protect the environment and other assets. However, where practicable, non-lethal measures may be explored for some animal species. Eradication will continue to be included in the aims for widely spread species and such action will be taken where feasible to do so. The government will continue to support research, such the ongoing study into contraception for grey squirrels to support this aim.

88) The Welsh Government will continue to work with key stakeholders to develop and enhance management of grey squirrel and muntjac deer aligning with the grey squirrel management action plan for Wales and Action plan for wild deer management in Wales.

15. Summary of responses relating to Appendix D – management measures for Signal Crayfish

89) There were a number of responses to the consultation that discussed the proposals set out in Appendix D. These came from a wide range of respondents including private individuals, academic research groups, commercial trappers, water management bodies, and conservation groups.

90) There was a wide range of views provided, supported by varying levels of evidence, from which a number of key themes were expressed. The key themes raised included regulation, enforcement, environmental risk, and the impact to businesses.

91) The idea that there should be tighter regulation in this area was put forward by a large number of the respondents. Responses differed, however, in their views on what form this regulation should take. Trappers, both commercial and private individuals, mainly wanted to see a more formalised regulatory system that would aim to professionalise the business, whilst NGOs and water management bodies wished to see an end to commercial trapping which they see as perpetuating the environmental impacts caused by this species.

92) There were also a number of respondents who felt that any form of further regulation was too restrictive. This view was also mainly held by those involved in the trapping of the species.

93) There were questions raised by some respondents as to why management measures did not extend to all invasive crayfish.

94) There were a range of views expressed over the enforcement of the management measures. The need for better research to allow for more effective and strategic enforcement was highlighted. Furthermore, respondents talked about the need for increased funding to ensure the effective enforcement of any management regime.

95) Many respondents questioned whether any licensing regime could be properly enforced, and felt that without a much higher level of engagement from enforcement bodies then the proposed regime could lead to further environmental impacts.

96) Some respondents felt that rules surrounding trapping should be relaxed, and thought that increased scrutiny on trappers from enforcement bodies was counterproductive to the aims set out in Appendix A.

97) Respondents also highlighted that strict biosecurity measures should be in place to prevent the further spread of the species.

98) Concerns were raised by a number of respondents that the continued commercial use of signal crayfish would only lead to further spread. This was highlighted in evidence provided by the International Association of Astacology (IAA) who provided a detailed explanation regarding the spread of signal crayfish within Sweden and the link between previously Signal crayfish free areas. They stated “Fisheries is not a method to control the impact and spread of IAS crayfish. It instead increases the spread and damage caused by IAS crayfish. This is based on 60 years’ experience in Sweden and Finland of the invasive North American Signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus). There is not a single published example where fisheries has resulted in the extinction of an IAS crayfish population (Hein et al. 2007. Freshwater Biology, 52(6), 1134-1146). Fisheries and handling of the catch has instead been proved to be the cause of further spread, despite good intentions to perform the control fishery under strict conditions in Sweden, Finland and Norway (Edsman & Schröder 2009. Action plan for noble crayfish 2008–2013. Fiskeriverket och Naturvårdsverket, Report 5955. ; Bohman, Ed. 2019. Swedish Crayfish Database. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Aquatic Resources).”

99) Some respondents called for a complete ban on commercial exploitation in exclusion zones. Their view was that commercial exploitation in these areas would encourage the further spread of the species, and that the focus in exclusion zones should be one of strict control. These respondents highlighted a correlation between trapping and the spread of the species. It was further expressed that commercial and hobby trapping should be prevented in exclusion zones and other ecologically sensitive areas, to reduce the risk of spread, whether through accident or intent.

100) Some respondents felt that the commercial use of live crayfish was a high risk to the environment. It was stated that any live movements would need to be biosecure, but concerns were raised over accidental escapes, or intentional releases of live specimens. Buglife specifically called for trapping to be limited to fisheries management, scientific research, or genuine eradication attempts in all areas, with no commercial use of the species to be encouraged. They strongly felt that continued sale would lead to further ecological damage.

101) There were also points raised over the need for a further review of the exclusion and containment zones, with a specific recommendation that the postcode approach be replaced with zones that consider a catchment-based approach.

102) Some respondents stated that it needed to be clear to businesses what actions would be allowed under any new regime. Also that any actions taken by businesses were biosecure, and that the continued trapping of crayfish was truly being done in a way that could be demonstrated to be a management measure.

103) Some respondents were in favour of the sale of crayfish, but it was stated that the assumption that there was no market for dead crayfish was incorrect. The Angling Trust responded specifically to this point by saying “We would question the evidence outlined in Paragraph 70 that states there is ‘little or no market for dead Signal crayfish’. Dead and pre-cooked crayfish tails are often used by hotels sold to them frozen…to our knowledge there are very few restaurants that keep live Signal crayfish on site for consumption.”

104) However, responses from those involved in trapping repeatedly made the point that live signal crayfish are important to the industry, and that there needs to be some ongoing incentive to catch crayfish. It was highlighted that trappers felt that they could have ongoing beneficial effects on the environment by removing signal crayfish, and that they should be able to continue to sell them alive. One response stated that they felt that the proposals in the consultation as set out would impact the crayfish industry, and would not help current businesses grow. There was a clear level of concern within the trapping industry raised over the impact that any tightening of restrictions in line with the Principal Regulation would have on their businesses, as well as the country’s ability to manage Signal crayfish through trapping efforts.

16. Government response relating to management measures for Signal crayfish (Appendix D)

105) As part of the consultation process, a series of stakeholder engagement sessions were undertaken to enable a greater understanding of the commercial use, impacts, and other associated concerns related to Signal crayfish in England and Wales.

106) Officials met with a range of stakeholders and experts made up of: private individuals, academic research groups, commercial trappers, water management bodies, conservation groups, NGOs and enforcement bodies. These focused meetings, along with the consultation responses, resulted in a number of amendments to the proposals set out in Appendix D of the consultation document.

107) When developing our proposals, the government has sought to prioritise mitigating further risk to the environment and ensuring that management measures are robust in their aims. Consideration was also taken of the real impact that major changes to the regulations on the commercial trade of this species will have on professional trappers in England in the short term. We also are of the view there is an on-going need for management of large and damaging populations of Signal crayfish in order to attempt to control these populations in a feasible, effective and economically viable way.

108) Following this further development of proposals, our position was initially set out in the interim response of 1 November 2019 (updated on 20 December 2019). Our position is as follows:

i. Exclusion Zones (in England and Wales) - The current policy of not allowing the commercial exploitation of Signal crayfish in the “exclusion zone”, (currently, commonly referred to as the “no-go area” as prescribed by the Schedule to the Prohibition of Keeping of Fish (Crayfish) Order 1996) will be maintained. This would mean that the status quo will be maintained, with trapping in the exclusion zones allowed only for conservation, scientific, or fisheries management purposes, and no commercial use of any kind permitted.

ii. Containment zones (in England) –Trapping of signal crayfish will be allowed in the containment zones (currently, commonly referred to as the “go area” under the Prohibition of Keeping of Fish (Crayfish) Order 1996) (where an authorisation has been granted), but sale of live Signal crayfish will not be permitted. Crayfish must be dispatched at the place of capture or taken to a processing facility which has a licence to handle live Signal crayfish. Facilities would not be licensed to obtain or receive crayfish taken from exclusion zones. This would not remove the opportunity for the sale of trapped and processed dead Signal crayfish, or prevent the exploration of alternative markets for dead Signal crayfish, such as in bait products, or animal feed (subject to the necessary treatment). It will also be possible under licence to trap for conservation, scientific, or fisheries management purposes in these zones.

iii. Containment zones (in Wales) –The commercial exploitation of Signal crayfish in the “containment zone”, (currently, commonly referred to as the “go area” as prescribed by the Schedule to the Prohibition of Keeping of Fish (Crayfish) Order 1996) will not be permitted. This would mean that the status quo will be maintained, with trapping in the containment zones allowed only for conservation, scientific, or fisheries management purposes. 109) These measures mean that individual trappers will not be allowed under any circumstances to move live specimens of this species further than the river bank, and will no longer be allowed to take live signal crayfish home for personal consumption. This sort of action does not contribute to the aims of management measures, and at best is selective harvesting of large individuals which could prove to have an unwanted negative effect in the long term. This sort of action also proves to be too high a risk in relation to the spread of this species. Therefore, actions involving the movement and keeping of live Signal Crayfish will only be lawful under licence. 110) In addition to the amendments above, Defra has decided to allow the continued, live export of Signal Crayfish, under limited conditions, from containment zones in England to allow businesses to adapt to the new regulatory regime.

111) This temporary licensing of the commercial exploitation of live Signal Crayfish in England will only be allowed under the following strict conditions:

i. that only licensed facilities set up for consolidation, purging, grading, freezing or processing of Signal Crayfish may seek an export licence;

ii. that export will only be allowed for a 2 year period as a transitional measure;

iii. that exported animals may only be sent to countries (whether within or outside the EU) where live import is lawful;

iv. that any transport is biosecure throughout the journey, with all animals being held in secure licensed premises and then securely packaged for transport in accordance with the requirements of EC Regulation 853/2004.

112) During the two year period, Defra will monitor how licences are being used, the extent and destination of export, any evidence on illegal sales, and reports of ecological damage, and will review evidence of how the industry is adapting. Individual licences will be revoked if there is evidence of non-compliance. All live exportation will end after this 2 year transitional period.

113) Under the IAS Regulation, it is possible to allow the temporary commercial use of a widely spread species, as part of management measures aimed at eradication, population control or containment of the species. Defra is therefore willing to allow this action in England for a limited period of time to allow business to adapt. The removal of Signal crayfish under licence is part of our overall management approach aimed at the population control of this species in England.

17. Annex A – Organisational respondents

Animal Aid

Angling Trust

BeastWatch UK

Buglife

Breedon on the Hill Parish Council

Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council

British Association for Shooting and Conservation

Balcombe Fly Fishers

Crayfish Capers

Coventry Wildlife Rescue

Community Invasive Non-Native (Species) Group

Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International

Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru / Natural Resources Wales

Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM)

Celtic Rainforests Wales Project

Confederation of Forest Industries (UK)

Country Land and Business Association

Devon Biodiversity Records Centre

Dee Invasive Non-Native Species Project

Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water

Dusters Ark

Dogs4rescue

Devon Invasive Species Initiataive (DISI)

Exmoor National Park Authority

Forestry Commission

Folly Wildlife Rescue

Gloucestershire County Council

Goodheart Animal Sanctuaries

Heritage LandCare

Hertfordshire Ecology

Institute of Tropical Biodiversity and Sustainable Development

Isle of Wight Catchment Partnership

International Association of Astacology

Lower Coquetdale Red Squirrels

London Wildlife Protection

London Invasive Species Initiative

New Forest Non-Native Plant Project

North Western Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (NWIFCA)

National Farmers Union (NFU)

Network Rail

Newcastle University

Natural England

National Gamekeepers’ Organisation

National Farmers’ Union of Cymru

Northumberland Rivers Trust

National Centre for Reptile Welfare

Peper Harow Park Fly Fishers Club

Penrith & District Red Squirrel Group

Property Care Association

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park

PBA Applied Ecology Ltd

Red Squirrels Northern England

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

Royal Forestry Society

Reptile & Exotic Pet Trade Association (REPTA)

Stowe School

SongBird Survival

Suckley Hills Stream Improvement Group

South West Lakes Trust

St Catharine’s College, Cambridge University

South West Water

Tiggywinkles Wildlife Hospital

Tyne Rivers Trust

The Warwick School, Surrey

The National Forest Company

The Wildlife Aid Foundation

The Starlight Trust

The British Deer Society

The Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association (OATA)

The Yorkshire Invasive Species Forum

Urban Squirrels

United Kingdom Crayfish Association

Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Vale wildlife hospital

Wandsworth Council

Woodland Trust

Wildlife and Countryside Link

West Cumbria Rivers Trust

18. Annex B – Management measure aims

- The intention of the aims set out below are working towards reducing the impact of these species on native biodiversity and ecosystem services, and wider socio-economic impacts.

18.1 Plants

Species:

- American skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus)

- Chilean rhubarb (Gunnera tinctoria)

- Curly waterweed (Lagarosiphon major)

- Floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides)

- Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)

- Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Nuttall’s waterweed (Elodea nuttallii)

- Parrot’s feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum)

Aims: To reduce further spread of these species, with localised eradication being carried out in high priority areas where possible. Examples of high priority areas might include: * sites designated for nature conservation purposes where rare native plants or animals are at threat * areas where new populations have become established and control is feasible * areas where there is a high risk of spread from primary sources of these species

18.2 Animals

Goose, deer and slider terrapins

Species:

- Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus)

- Muntjac deer (Muntiacus reevesi)

- All subspecies of Trachemys scripta (also known as “slider terrapins”) - this includes all subspecies of Trachemys scripta such as yellow-bellied slider, red-eared slider, Cumberland slider, and common slider

Aims:

- To control the current wild population of this species, to reduce its further spread and to eradicate in the wild where possible using humane measures, where outcomes are achievable and benefits are sustainable.

- To reduce the number of individuals in captivity over time.

Squirrel

Species:

- Grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)

Aims:

- To control the current wild population of this species, to reduce its further spread and to eradicate in the wild where possible using humane measures, where outcomes are achievable and benefits are sustainable.

- To prevent establishment on islands where the species cannot colonise naturally.

- To prevent establishment in areas that are the preserve of red squirrel populations.

- To reduce the number of individuals in captivity over time.

Crab and crayfish

Species:

- Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis)

- Signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus)

Aims:

- To reduce further spread of the species and mitigate its impacts.

- To eradicate in areas where using humane measures, where outcomes are achievable and benefits are sustainable.